So what are the best fat burning exercises in the gym that you need to include in your training?

Losing body fat is one of the most common fitness goals, yet it remains among the most misunderstood. Many people rely solely on cardio machines or restrictive diets, but science shows that structured, high-intensity training combining resistance and cardiovascular elements is the most effective way to increase energy expenditure and enhance fat loss.

This article examines ten of the most effective fat-burning exercises in the gym, each supported by scientific evidence on their physiological impact.

Understanding Fat Loss

Before breaking down the exercises, it is important to clarify how fat loss occurs. The body burns calories through basal metabolic rate, thermic effect of food, and physical activity. To reduce fat mass, a person must sustain a negative energy balance—burning more energy than consumed. Exercise plays a crucial role not only by increasing caloric expenditure during activity but also by elevating post-exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC), enhancing muscle mass (which raises resting metabolic rate), and improving insulin sensitivity.

1. High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) on the Treadmill

HIIT involves alternating between periods of intense effort and active recovery. For example, sprinting for 30 seconds followed by 90 seconds of walking.

Research has consistently shown HIIT to be superior to steady-state cardio for fat reduction. A landmark study by Tremblay et al. (1994) found that participants engaging in 15 weeks of HIIT lost significantly more subcutaneous fat compared to those performing 20 weeks of steady-state endurance training, despite lower total energy expenditure. This effect is attributed to elevated EPOC, increased mitochondrial density, and improved fat oxidation.

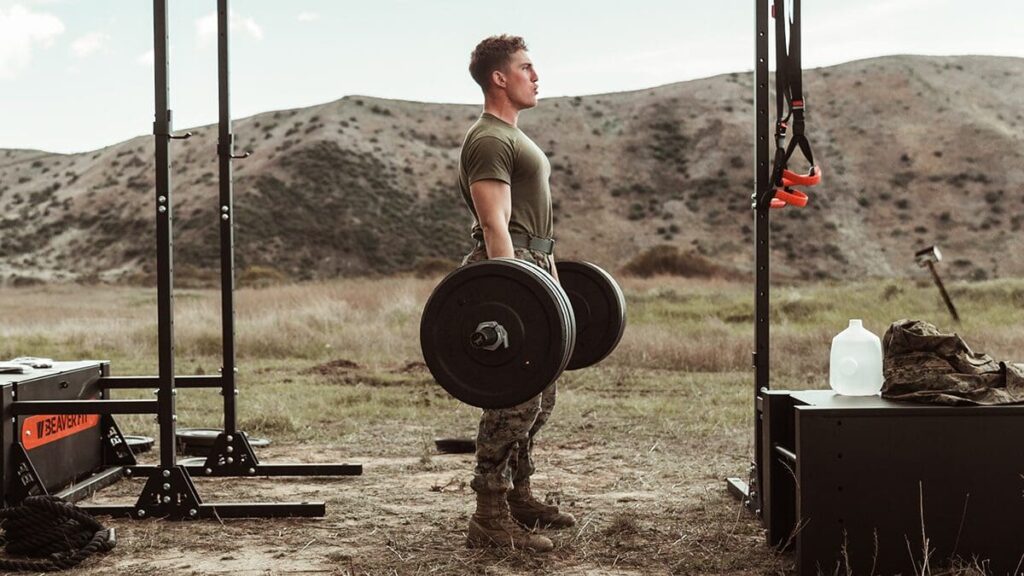

2. Fat Burning Exercises in the Gym: Barbell Deadlifts

The deadlift is a compound movement engaging multiple large muscle groups, including the posterior chain, core, and grip musculature. Heavy compound lifts like deadlifts are highly metabolically demanding, leading to increased energy expenditure both during and after training.

A study by Schuenke et al. (2002) demonstrated that resistance training with large compound lifts significantly elevates resting energy expenditure for up to 48 hours post-exercise, contributing to fat loss. Deadlifts, in particular, recruit vast muscle mass, making them one of the most calorie-intensive strength exercises.

3. Fat Burning Exercises in the Gym: Kettlebell Swings

Kettlebell swings combine strength and power with cardiovascular conditioning. They require explosive hip extension, engaging glutes, hamstrings, core, and shoulders.

Farrar et al. (2010) reported that a 20-minute kettlebell swing workout burned approximately 20.2 calories per minute, comparable to running at a 6-minute mile pace. Additionally, kettlebell training improves aerobic capacity and muscular endurance, supporting long-term fat-burning adaptations.

4. Fat Burning Exercises in the Gym: Rowing Machine Intervals

The rowing ergometer provides full-body conditioning, engaging upper and lower body muscles while maintaining a high cardiovascular demand. Intervals of intense rowing followed by short rest periods maximize caloric burn.

Studies by Hagerman (1984) showed elite rowers had higher maximal oxygen uptake than runners and cyclists, underlining the metabolic demands of rowing. For gym-goers, rowing intervals offer a joint-friendly yet highly effective fat-burning stimulus.

5. Battle Ropes

Battle ropes are a versatile tool for high-intensity training. Alternating waves, slams, and circles engage upper body, core, and lower body stabilizers while elevating heart rate.

A study by Ratamess et al. (2015) found that a 10-minute battle rope session elicited heart rates above 85% of maximum and metabolic equivalents (METs) indicative of vigorous-intensity exercise. Such intensity contributes to both acute calorie burn and post-exercise metabolic elevation.

6. Weighted Sled Pushes

Pushing a sled loaded with weight requires large muscle recruitment, particularly from the legs, hips, and core, while keeping heart rate elevated. Unlike traditional lifts, sled pushes involve concentric-only muscle actions, reducing muscle soreness while still maximizing energy expenditure.

Escamilla et al. (2012) demonstrated that sled pushing enhances sprint performance and metabolic conditioning. Its ability to provide high-intensity, low-impact training makes it an optimal choice for fat loss.

7. Fat Burning Exercises in the Gym: Circuit Weight Training

Circuit training involves moving through resistance exercises with minimal rest. This method maintains elevated heart rates while providing muscular stimulus.

Gettman et al. (1978) reported that circuit weight training significantly increased energy expenditure, reaching 8 METs, comparable to running at moderate intensity. Furthermore, the combination of resistance and cardiovascular stimulus enhances both fat oxidation and muscle preservation.

8. Fat Burning Exercises in the Gym: Stair Climbing (Stair Mill)

The stair mill provides continuous resistance, requiring major lower body muscle engagement. Unlike flat treadmill walking, stair climbing increases relative oxygen consumption and caloric burn.

Porcari et al. (2014) observed that stair climbing elicited significantly higher oxygen uptake compared to treadmill walking at similar speeds, underlining its effectiveness as a fat-burning tool. It also strengthens lower body musculature, supporting long-term metabolic benefits.

9. Burpees

The burpee is a bodyweight conditioning exercise combining squat, plank, push-up, and jump in a single movement. Its full-body involvement makes it extremely demanding.

Calorie expenditure estimates place burpees at 10–15 calories per minute depending on intensity and body weight (McRae et al., 2012). Moreover, burpees challenge both aerobic and anaerobic systems, boosting fat oxidation and cardiovascular fitness simultaneously.

10. Fat Burning Exercises in the Gym: Stationary Bike Sprints

Cycling sprints offer low-impact, joint-friendly conditioning. Like treadmill sprints, bike sprints maximize energy expenditure and elevate EPOC.

A study by Burgomaster et al. (2008) found that short-term sprint interval training increased skeletal muscle oxidative capacity and fat metabolism as effectively as endurance training, but with significantly lower time commitment. For those with limited training time, bike sprints are a highly efficient fat-burning option.

Integrating These Exercises into a Training Program

To maximize fat loss, these exercises should be combined strategically. For example, alternating resistance-based movements (deadlifts, kettlebell swings, sled pushes) with metabolic conditioning (HIIT, battle ropes, rowing) ensures both muscular adaptation and high caloric burn. Frequency should be 3–5 sessions per week, with intensity tailored to individual fitness levels. Importantly, exercise must be paired with appropriate nutrition and recovery for optimal results.

Fat Burning Exercises in the Gym: Key Takeaways

| Exercise | Primary Muscles Involved | Caloric Burn & Fat-Loss Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| HIIT Treadmill Sprints | Legs, core, cardiovascular system | High EPOC, superior fat oxidation |

| Barbell Deadlifts | Posterior chain, grip, core | Elevated metabolism up to 48h post-exercise |

| Kettlebell Swings | Glutes, hamstrings, shoulders | ~20 cal/min, power + cardio effect |

| Rowing Machine Intervals | Full body | High VO2 demand, joint-friendly |

| Battle Ropes | Upper body, core | Vigorous intensity, >85% HRmax |

| Weighted Sled Pushes | Legs, hips, core | High-intensity, concentric only |

| Circuit Weight Training | Multiple groups | 8 METs, combines cardio + strength |

| Stair Climbing | Lower body | Higher VO2 than treadmill walking |

| Burpees | Full body | 10–15 cal/min, aerobic + anaerobic |

| Bike Sprints | Legs, cardiovascular | Boosts fat oxidation efficiently |

References

- Burgomaster, K.A., Howarth, K.R., Phillips, S.M., Rakobowchuk, M., MacDonald, M.J., McGee, S.L. and Gibala, M.J., 2008. Similar metabolic adaptations during exercise after low volume sprint interval and traditional endurance training in humans. The Journal of Physiology, 586(1), pp.151–160.

- Escamilla, R.F., Fleisig, G.S., Zheng, N., Barrentine, S.W., Wilk, K.E. and Andrews, J.R., 2012. Effects of sled towing on sprint time, speed, and acceleration. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(5), pp.1186–1194.

- Farrar, R.E., Mayhew, J.L. and Koch, A.J., 2010. Oxygen cost of kettlebell swings. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(4), pp.1034–1036.

- Gettman, L.R., Ayres, J.J., Pollock, M.L. and Jackson, A., 1978. The effect of circuit weight training on strength, cardiorespiratory function, and body composition of adult men. Medicine and Science in Sports, 10(3), pp.171–176.

- Hagerman, F.C., 1984. Applied physiology of rowing. Sports Medicine, 1(4), pp.303–326.

- McRae, G., Payne, A., Zelt, J.G.E., Scribbans, T.D., Jung, M.E. and Gurd, B.J., 2012. Extremely low volume, whole-body aerobic–resistance training improves aerobic fitness and muscular endurance in females. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 37(6), pp.1124–1131.

- Porcari, J.P., Doberstein, S.T., Foster, C., Radtke, K., Cress, M.L. and Schmidt, K., 2014. Exercise responses using a stair climber. Journal of Exercise Science and Fitness, 12(2), pp.55–61.

- Ratamess, N.A., Rosenberg, J.G., Klei, S., Dougherty, B.M., Kang, J., Smith, C.R., Ross, R.E., Faigenbaum, A.D. and Kraemer, W.J., 2015. Comparison of the acute metabolic responses to traditional resistance, body-weight, and battling rope exercises. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(1), pp.47–57.

- Schuenke, M.D., Mikat, R.P. and McBride, J.M., 2002. Effect of an acute period of resistance exercise on excess post-exercise oxygen consumption: implications for body mass management. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 86(5), pp.411–417.

- Tremblay, A., Simoneau, J.A. and Bouchard, C., 1994. Impact of exercise intensity on body fatness and skeletal muscle metabolism. Metabolism, 43(7), pp.814–818.