Building a powerful, well-defined lower chest isn’t just about aesthetics. A well-developed lower pectoral region improves total chest mass, balance, pressing strength, and shoulder stability. Yet, it’s often neglected due to limited understanding and poorly chosen exercises.

In this article, we dive deep into the three best exercises for developing a jacked lower chest. Each is backed by biomechanical reasoning and supported by scientific studies. This is not fluff—just hard science and proven programming to maximize hypertrophy.

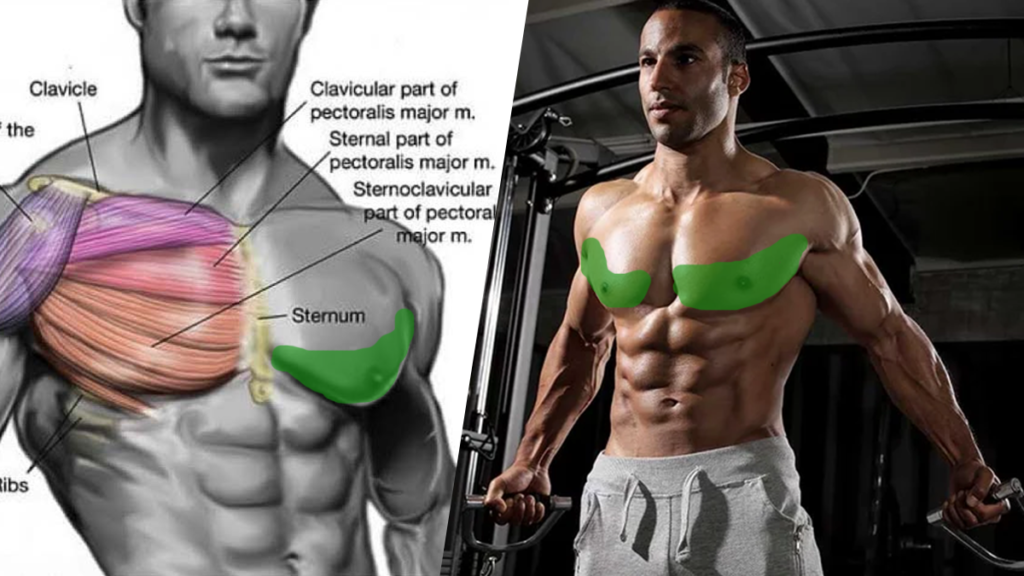

Understanding Lower Chest Anatomy

The Role of the Pectoralis Major

The chest is dominated by the pectoralis major, which has two distinct heads: the clavicular head (upper chest) and the sternal head (middle and lower chest). The lower chest fibers, sometimes called the abdominal fibers, originate from the sternum and upper six ribs and insert into the humerus.

Activation of these fibers is enhanced when the shoulder moves in shoulder extension and adduction, especially when the arms move downward and across the body. Hence, decline angles and downward pushing or fly movements best stimulate this region.

[wpcode id=”229888″]Why Targeting the Lower Chest Matters

Most lifters emphasize flat and incline bench pressing, developing the upper and mid-chest while neglecting the lower fibers. This leads to an imbalanced chest with a flatter or underdeveloped lower portion. From a performance standpoint, strengthening the lower pectorals contributes to pressing force, especially in dips and deep push-up variations. From an aesthetic perspective, a thick lower chest gives the illusion of a fuller, more powerful torso.

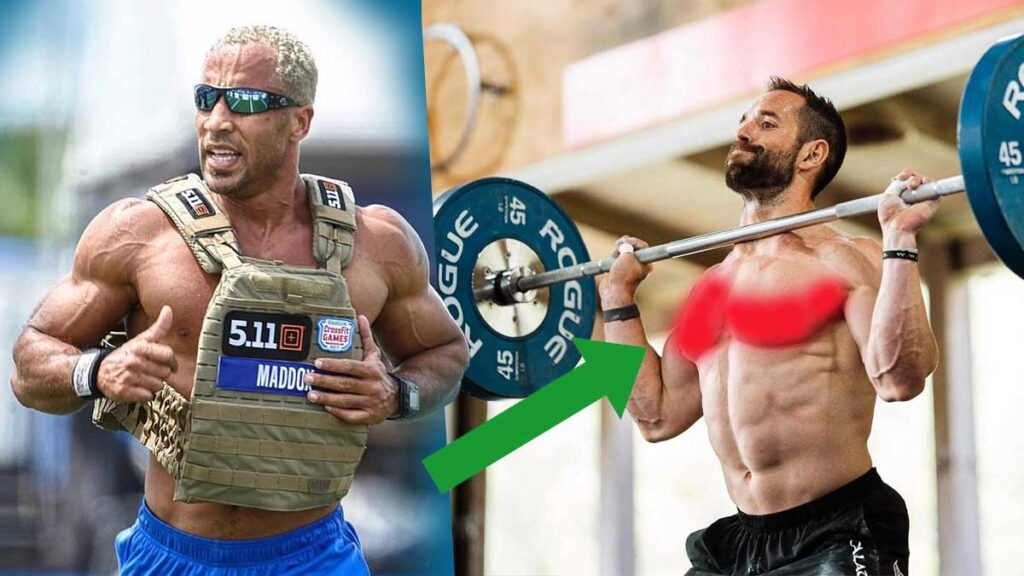

Exercise #1: Decline Barbell Bench Press

Biomechanical Advantage

The decline barbell bench press is the king of lower chest exercises. The decline angle (usually 15–30 degrees) places the arms in a downward arc, mimicking the direction of the lower pectoral fibers and maximizing fiber recruitment. A study by Trebs et al. (2010) compared EMG activity in different bench angles and found that the decline bench elicited significantly greater activation in the lower portion of the pectoralis major than flat or incline variations.

Execution and Cues

Set the bench to a 15–30-degree decline. Grip the bar slightly wider than shoulder-width. Lower the bar to the lower chest—roughly at or just above the xiphoid process—and press upward following the same path. Ensure the scapulae are retracted and depressed throughout to avoid shoulder stress.

Program Prescription

Start your chest session with this compound lift for maximum output. Use moderate to heavy loads (70–85% of 1RM) for 3–4 sets of 6–10 reps. Prioritize controlled eccentrics and avoid bouncing the bar off the chest.

Scientific Support

In addition to Trebs et al., Glass and Armstrong (1997) showed that decline pressing, due to its favorable angle and reduced shoulder strain, allows lifters to engage the lower pectorals more efficiently while limiting anterior deltoid involvement.

Exercise #2: Chest Dips (With Forward Lean)

Biomechanical Advantage

Dips are a compound, bodyweight movement that becomes a lower chest hypertrophy powerhouse when executed correctly. The key is to lean the torso forward and allow the elbows to flare slightly to increase chest involvement. This variation puts the shoulder into extension while the arm moves downward and inward—ideal mechanics for lower chest activation.

Execution and Cues

Use parallel bars. Begin with arms locked out, body suspended. Lean the torso forward at roughly a 30–45-degree angle and allow your chest to lead the descent. Lower slowly until your upper arms are at or below parallel, then press back to the top. Maintain a consistent lean to keep tension on the chest rather than shifting to the triceps.

Use a dip belt for added resistance when bodyweight becomes too easy. Avoid staying upright or locking the elbows forcefully, as this turns the movement into a triceps-dominant pattern.

Program Prescription

Include dips after your primary pressing movement. Perform 3–4 sets of 8–15 reps, progressing to weighted dips once you can handle 12–15 clean reps. Focus on controlled reps and maintaining torso angle throughout.

Scientific Support

Electromyographic analysis by Oliveira et al. (2009) confirmed that dipping with a forward torso angle enhances pectoralis major activation compared to upright dips. This position shifts load from the triceps to the chest, particularly emphasizing the sternal fibers.

Exercise #3: High-to-Low Cable Crossover

Biomechanical Advantage

While compound lifts provide the mass-building stimulus, isolation exercises like the high-to-low cable crossover fine-tune hypertrophy by allowing full range and peak contraction in the target muscle. By pulling the arms from a high, outstretched position down and across the body at a downward angle, you perfectly align with the lower pectoral fibers.

Cables provide constant tension throughout the movement, unlike dumbbells or machines. Additionally, the unilateral nature of this exercise allows for correction of muscle imbalances between sides.

Execution and Cues

Set the cables at shoulder height or slightly above. Grasp the handles and step forward into a staggered stance. With a slight bend in the elbows, pull the handles downward and inward toward the hips, focusing on squeezing the lower pecs. Pause briefly at the bottom before returning under control.

Avoid rounding the shoulders or using momentum. Keep the chest proud and ensure movement comes from the pectorals, not the deltoids.

Program Prescription

Cable crossovers should be used toward the end of your chest session. Perform 3–4 sets of 10–15 reps, focusing on slow eccentrics and strong contractions. Drop sets and rest-pause sets can be used here to push the metabolic stress and hypertrophic response.

Scientific Support

A study by Schick et al. (2010) demonstrated that cable fly variations allowed for higher lower chest fiber engagement during the concentric phase than flat or incline dumbbell flies, largely due to the direction of resistance and control over arm path.

Supporting Research and Practical Application

Muscle Fiber Recruitment and Hypertrophy

Hypertrophy is highly influenced by motor unit recruitment, mechanical tension, and metabolic stress. Studies show that angles and direction of resistance significantly influence muscle activation patterns (Schoenfeld, 2010). Therefore, choosing exercises that mechanically align with lower pectoral fibers increases the recruitment of the desired region.

Programming Strategies for Lower Chest Emphasis

To maximize lower chest development:

- Start sessions with compound lifts (Decline Bench or Weighted Dips) when energy is highest.

- Use isolation work (Cable Crossovers) to fully fatigue the muscle fibers.

- Train with a mix of mechanical tension (heavy sets of 6–10) and metabolic stress (higher rep sets of 12–15).

- Rest between sets should vary: 2–3 minutes for heavy presses, 60–90 seconds for accessory work.

Frequency should be based on total volume and recovery capacity. Two chest-focused sessions per week, with at least 10–12 sets targeting the lower chest, is optimal for most intermediate lifters (Schoenfeld et al., 2016).

Avoiding Common Mistakes

Many lifters make the mistake of:

- Using flat or incline pressing only, leaving the lower chest under-stimulated.

- Performing dips too upright, shifting emphasis to the triceps.

- Using poor form in crossovers—rounding the shoulders or shortening the range of motion.

Prioritize form and intent over load. Lower chest training must be deliberate.

Advanced Tips for Maximizing Lower Chest Gains

Use Pre-Fatigue Techniques

Start with high-to-low cable crossovers to fatigue the lower pecs, then move into decline pressing. This enhances mind-muscle connection and ensures the lower chest is heavily involved during compound lifts.

Manipulate Tempo

Slowing the eccentric (lowering) portion of the lift increases time under tension, which promotes hypertrophy. Try a 3-second negative on dips and decline presses.

Isometric Holds

Hold the bottom position of cable crossovers for 1–2 seconds to enhance motor unit recruitment. Similarly, pause at the deepest point in dips for improved control and fiber activation.

Utilize Reverse Pyramid Training

Start with the heaviest set first when energy and nervous system readiness are highest, then reduce weight in subsequent sets while increasing reps. This optimizes both strength and hypertrophy outcomes.

Conclusion

A well-developed lower chest transforms your physique and improves pressing performance. By targeting the sternal fibers of the pectoralis major with biomechanically aligned exercises, you stimulate optimal growth. The decline bench press, forward-leaning dips, and high-to-low cable crossovers each offer unique advantages when programmed intelligently. Backed by science and decades of bodybuilding wisdom, these exercises should be staples in any serious training routine aiming for a jacked lower chest.

Bibliography

Glass, S. C. and Armstrong, T. (1997). Electromyographical activity of the pectoralis muscle during incline and decline bench presses. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 11(3), pp.163–167.

Oliveira, L. F., et al. (2009). Activation of the pectoralis major in bench press variations. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(7), pp.2054–2058.

Schick, E. E., et al. (2010). Comparison of muscle activation during bench press and cable cross-over exercises. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 26(4), pp.443–448.

Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), pp.2857–2872.

Schoenfeld, B. J., Ogborn, D. and Krieger, J. W. (2016). Effects of resistance training frequency on measures of muscle hypertrophy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 46(11), pp.1689–1697.

Trebs, A. A., Brandenburg, J. P. and Pitney, W. A. (2010). An electromyographic analysis of three muscles surrounding the shoulder joint during the performance of a chest press exercise at varying angles. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(7), pp.1925–1930.