A strong back is the cornerstone of athletic performance, posture, and injury prevention. Yet, many lifters unknowingly undermine their progress by focusing on the wrong exercises, neglecting muscular balance, or misunderstanding the science of adaptation.

This article uncovers three science-backed secrets to build a stronger back in the gym, based on current evidence in exercise physiology, biomechanics, and sports science.

Understanding the Back: Structure and Function

The back is a complex system of muscles, tendons, and neural pathways that coordinate movement, stability, and force transmission. The major muscle groups include:

- Latissimus dorsi – the largest back muscle, responsible for shoulder adduction and extension.

- Trapezius – stabilizes and moves the scapula, critical for shoulder health.

- Rhomboids – retract and stabilize the shoulder blades.

- Erector spinae – maintain spinal extension and resist flexion.

- Posterior deltoids and rotator cuff muscles – support shoulder integrity and upper-back mechanics.

Research shows that developing these muscles in balance improves not only strength and size but also reduces injury risk and enhances functional performance across lifts such as the deadlift, row, and pull-up (Schoenfeld, 2010).

Secret 1: Prioritize Pulling Volume and Movement Variety

The Volume Principle

Muscle hypertrophy and strength gains are largely driven by total weekly training volume—defined as sets × reps × load. Schoenfeld et al. (2019) found that performing 10+ sets per muscle group per week produced significantly greater hypertrophy than lower volumes. For the back, this means lifters should program at least 12–18 total working sets weekly across different movement patterns.

Horizontal vs. Vertical Pulling

To build a stronger back in the gym, lifters must include both horizontal and vertical pulling movements. Each pattern targets different muscle fibers and enhances scapular control:

- Horizontal pulls (e.g., barbell rows, cable rows, inverted rows) emphasize the mid-back, rhomboids, and rear deltoids.

- Vertical pulls (e.g., pull-ups, lat pulldowns) prioritize the latissimus dorsi and lower traps.

A study by Andersen et al. (2014) demonstrated that combining both planes of motion led to superior muscle activation and greater functional strength compared to focusing on one direction alone.

Evidence-Based Programming Example

An optimal weekly split might include:

- Day 1 (Vertical Focus): Weighted pull-ups, neutral-grip pulldowns, straight-arm pulldowns.

- Day 2 (Horizontal Focus): Barbell rows, single-arm dumbbell rows, face pulls.

Maintaining this variety ensures balanced development of both superficial and deep back musculature.

Secret 2: Train the Posterior Chain and Core Synergy

The Forgotten Synergy

A strong back does not function in isolation. The posterior chain—comprising the glutes, hamstrings, and spinal erectors—works synergistically with the lats and traps to stabilize and transfer power. McGill et al. (2009) demonstrated that spinal stiffness and coordinated core activation directly influence back muscle performance and resilience against injury.

Compound Lifts as Neural Drivers

Multi-joint exercises such as deadlifts, Romanian deadlifts, and good mornings stimulate high motor unit recruitment across the posterior chain. These lifts enhance neural drive, mechanical tension, and intermuscular coordination (Campos et al., 2002).

- Conventional deadlift: Maximal loading potential for strength.

- Romanian deadlift: Emphasizes eccentric loading, promoting fascicle lengthening and hypertrophy.

- Good morning: Reinforces spinal stability and glute-hamstring engagement.

The Core as a Power Transmitter

Training the core to resist motion—anti-flexion, anti-extension, and anti-rotation—has been shown to enhance back strength transfer. Exercises such as planks, Pallof presses, and bird dogs improve intra-abdominal pressure, protecting the spine and allowing for greater force production through the posterior chain (Behm et al., 2010).

Programming Integration

Incorporate 2–3 compound lifts per week and pair them with core-stability drills to build structural strength that supports back training longevity and output.

Secret 3: Optimize Mind-Muscle Connection and Eccentric Control

The Neuromuscular Connection

The mind-muscle connection (MMC)—the conscious activation of specific muscles during exercise—has measurable effects on muscle recruitment and hypertrophy. A study by Calatayud et al. (2016) found that lifters who focused on contracting their lats during pulldowns achieved significantly greater EMG activation than those who did not.

To build a stronger back in the gym, athletes should perform slower, controlled repetitions and focus on scapular retraction, depression, and maintaining tension through the range of motion.

The Science of Eccentric Loading

Eccentric (lengthening) contractions create more muscle damage and mechanical tension than concentric phases (Franchi et al., 2017). This microdamage triggers satellite cell activation, a key process in muscle remodeling and growth.

Integrating slow eccentrics—such as 3–4 second lowering phases on pull-ups or rows—amplifies hypertrophic signaling without requiring additional load.

Practical Application

- Pull-ups: 2-second concentric pull, 3-second eccentric lower.

- Bent-over rows: 1-second lift, 3-second controlled descent.

- Machine rows: Pause at peak contraction for 1 second before lowering.

Consistent focus on MMC and eccentric control refines neural efficiency and maximizes the mechanical work performed by the target musculature.

Beyond Strength: Injury Prevention and Longevity

Scapular Stability

Scapular dysfunction is a common precursor to shoulder and upper-back pain. Exercises such as face pulls, band pull-aparts, and YTWs strengthen the lower traps and rhomboids, maintaining scapulohumeral rhythm (Ludewig & Reynolds, 2009).

Balanced Shoulder Mechanics

Overemphasis on pressing movements (e.g., bench press) can lead to anterior shoulder dominance and protracted scapulae. Counterbalancing with pulling volume in a 2:1 pull-to-push ratio restores shoulder stability and reduces impingement risk (Cools et al., 2014).

Recovery and Load Management

Back strength gains depend on recovery and progressive overload. Studies show that muscle protein synthesis peaks 24–48 hours post-training (Damas et al., 2016), emphasizing the importance of nutrition, sleep, and gradual load increments of 2–5% weekly to prevent overtraining.

Periodization for Maximum Back Strength

Linear vs. Undulating Approaches

While linear periodization gradually increases load over time, undulating periodization—alternating intensity and volume across sessions—may produce superior strength and hypertrophy outcomes (Rhea et al., 2002).

Example weekly structure:

- Day 1 (Heavy): 4×6 pull-ups, 4×5 barbell rows.

- Day 2 (Moderate): 3×10 dumbbell rows, 3×12 face pulls.

- Day 3 (Light/Volume): 3×15 cable rows, 3×15 reverse flyes.

This strategy ensures continuous adaptation by stimulating multiple muscular and neural pathways.

Nutrition and Supplementation for Back Development

Protein and Amino Acids

Adequate protein intake (1.6–2.2 g/kg/day) supports muscle protein synthesis, particularly following resistance training (Morton et al., 2018). Fast-digesting whey protein post-workout can accelerate recovery.

Creatine Monohydrate

Creatine enhances ATP resynthesis during high-intensity efforts, leading to improved performance in compound lifts critical for back strength (Branch, 2003).

Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Recovery

Omega-3 supplementation may reduce exercise-induced inflammation and improve muscle function (Smith et al., 2011).

Conclusion: The Science of Building a Stronger Back

Building a stronger back in the gym requires more than heavy lifting—it demands intelligent programming, technical precision, and physiological understanding. Prioritize pulling variety and volume, integrate posterior chain synergy, and master the neuromuscular and eccentric aspects of movement.

These scientifically grounded principles will not only enhance back strength but improve posture, athletic performance, and long-term resilience.

Key Takeaways

| Principle | Key Actions | Scientific Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Volume & Variety | Perform 12–18 weekly sets; include horizontal and vertical pulls | Higher training volume leads to greater hypertrophy (Schoenfeld et al., 2019) |

| Posterior Chain & Core | Integrate deadlifts, RDLs, and anti-rotation core drills | Enhances spinal stability and neural coordination (McGill et al., 2009) |

| Mind-Muscle & Eccentric Focus | Control tempo, emphasize lats and scapular movement | Improves EMG activation and hypertrophic signaling (Calatayud et al., 2016) |

| Injury Prevention | Maintain 2:1 pull-to-push ratio, train lower traps | Supports shoulder mechanics and posture (Cools et al., 2014) |

| Periodization & Recovery | Use undulating loads and ensure 48-hour recovery | Maximizes adaptation and prevents overtraining (Rhea et al., 2002) |

References

- Andersen, V., Fimland, M.S., Wiik, E., et al. (2014). Effects of horizontal and vertical pulling exercises on muscle activation and strength development. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(12), 3326–3333.

- Behm, D.G., Drinkwater, E.J., Willardson, J.M., Cowley, P.M. (2010). The use of instability to train the core musculature. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 35(1), 91–108.

- Branch, J.D. (2003). Effect of creatine supplementation on body composition and performance: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 13(2), 198–226.

- Calatayud, J., Borreani, S., Colado, J.C., et al. (2016). Muscle activation during bench press and push-up at various loads and stable vs. unstable conditions. European Journal of Sport Science, 16(6), 1–8.

- Campos, G.E.R., Luecke, T.J., Wendeln, H.K., et al. (2002). Muscular adaptations in response to three different resistance-training regimens. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 88(1-2), 50–60.

- Cools, A.M., Dewitte, V., Lanszweert, F., et al. (2014). Rehabilitation of scapular muscle balance: Which exercises to prescribe? American Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(8), 1906–1917.

- Damas, F., Phillips, S.M., Libardi, C.A., et al. (2016). Resistance training-induced changes in integrated myofibrillar protein synthesis are related to hypertrophy. Journal of Physiology, 594(18), 5209–5223.

- Franchi, M.V., Reeves, N.D., Narici, M.V. (2017). Skeletal muscle remodeling in response to eccentric vs. concentric loading: Morphological, molecular, and metabolic adaptations. Frontiers in Physiology, 8, 447.

- Ludewig, P.M., Reynolds, J.F. (2009). The role of scapular dysfunction in shoulder impingement syndrome. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 39(2), 90–104.

- McGill, S.M., Karpowicz, A., Fenwick, C.M.J., Brown, S.H.M. (2009). Exercises for the torso performed in a standing posture: Spine and hip motion and muscle activity. Physical Therapy, 89(6), 627–643.

- Morton, R.W., Murphy, K.T., McKellar, S.R., et al. (2018). A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training–induced gains in muscle mass and strength. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(6), 376–384.

- Rhea, M.R., Ball, S.D., Phillips, W.T., Burkett, L.N. (2002). A comparison of linear and daily undulating periodized programs with equated volume and intensity for strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 16(2), 250–255.

- Schoenfeld, B.J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857–2872.

- Schoenfeld, B.J., Ogborn, D., Krieger, J.W. (2019). Dose-response relationship between weekly resistance training volume and increases in muscle mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 37(3), 257–264.

- Smith, G.I., Atherton, P., Reeds, D.N., et al. (2011). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids augment the muscle protein anabolic response to hyperinsulinemia-hyperaminoacidemia in healthy young and middle-aged men and women. Clinical Science, 121(6), 267–278.

About the Author

Robbie Wild Hudson is the Editor-in-Chief of BOXROX. He grew up in the lake district of Northern England, on a steady diet of weightlifting, trail running and wild swimming. Him and his two brothers hold 4x open water swimming world records, including a 142km swim of the River Eden and a couple of whirlpool crossings inside the Arctic Circle.

He currently trains at Falcon 1 CrossFit and the Roger Gracie Academy in Bratislava.

image sources

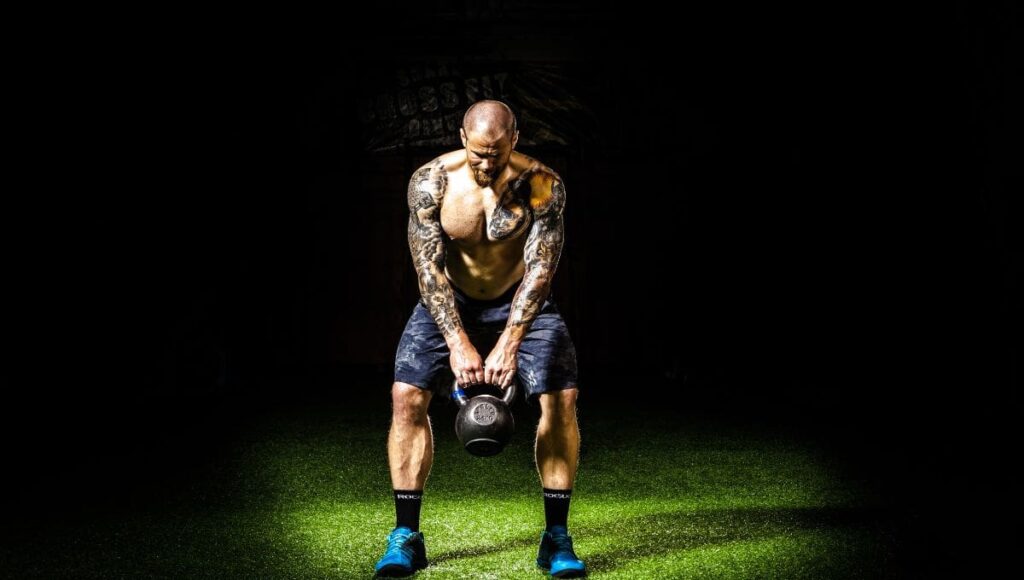

- Kettlebell swing: Binyamin Mellish on Pexels