Getting truly strong is not about secrets, gimmicks, or trendy workouts. Strength is a long-term biological adaptation driven by consistent exposure to mechanical tension, intelligent programming, sufficient recovery, and adequate nutrition. Decades of exercise science research give us very clear principles on how humans become stronger — and they are far simpler than most people think.

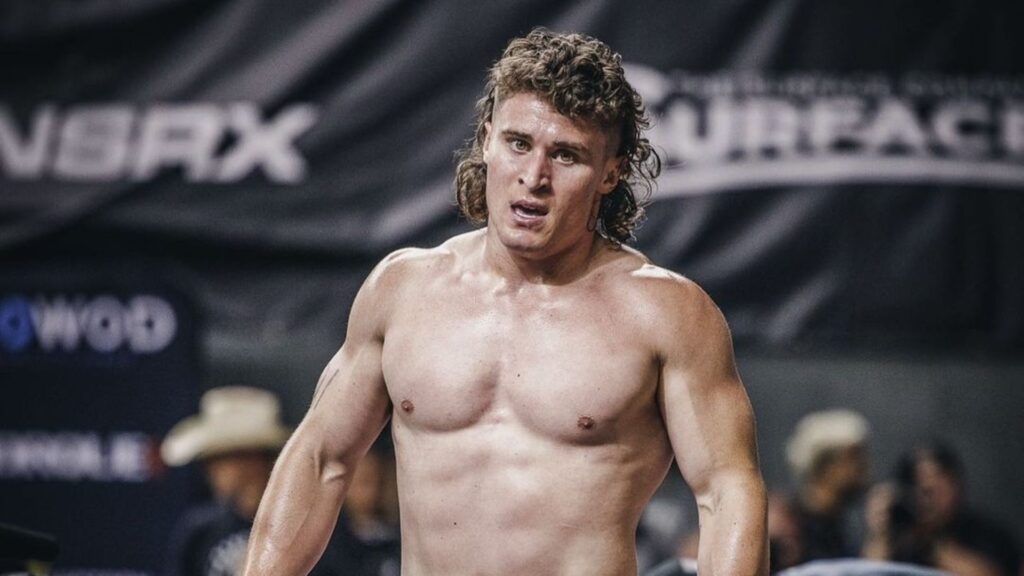

This article lays out five evidence-based tips to help you get super strong in 2026. These are not shortcuts. They are the same principles used by elite powerlifters, Olympic weightlifters, CrossFit athletes, and strength coaches around the world — scaled so any committed person can apply them.

Each tip is grounded in peer-reviewed research, explained in clear language, and designed to be practical. If you follow these principles consistently for the next year, your strength potential will look very different by the end of 2026.

Tip 1: Prioritize Progressive Overload Above Everything Else

What Progressive Overload Really Means

Progressive overload is the gradual increase of stress placed on the body during training. This stress can come from lifting heavier weights, performing more repetitions, increasing total training volume, improving exercise difficulty, or reducing rest times — but load progression remains the most direct driver of maximal strength.

Strength gains occur when muscles and the nervous system adapt to forces they are not yet accustomed to handling. If the training stimulus stays the same, the body has no biological reason to get stronger. Progressive overload provides the signal for adaptation.

Research consistently shows that increasing external load over time is a primary determinant of strength development. A landmark meta-analysis by Peterson et al. found that training programs emphasizing progressive overload led to significantly greater strength gains than static-load programs.

Mechanical Tension Is the Key Stimulus

Mechanical tension — the force produced by muscles when they contract against resistance — is the primary driver of strength and muscle growth. Heavy loads produce higher levels of mechanical tension, especially when lifted through full ranges of motion.

Studies using muscle biopsies and electromyography show that high mechanical tension stimulates increased motor unit recruitment, particularly of high-threshold motor units responsible for producing maximal force. This neural adaptation is one of the earliest and most important contributors to strength gains, especially in the first months of training.

Without progressive increases in tension, neural drive plateaus and muscle fiber adaptations slow dramatically.

How to Apply Progressive Overload in Practice

Progressive overload does not mean adding weight every single workout. That approach often leads to burnout or injury. Instead, progression should be planned over weeks and months.

Effective strategies include:

• Increasing load by 2–5 percent once all target reps are achieved

• Adding one to two total reps per set before increasing weight

• Increasing total weekly volume gradually

• Improving bar speed or technique at the same load before increasing weight

Long-term strength progression is best achieved through structured programming that cycles volume and intensity. Research on periodization consistently shows superior strength outcomes compared to non-periodized training.

Why Many People Fail at Overload

Many lifters train hard but fail to track performance. Without data, progression becomes random. Studies show that self-selected training loads often remain too light to stimulate maximal strength gains.

Tracking sets, reps, and loads ensures that progression is objective rather than emotional. Strength is built by numbers, not feelings.

Tip 2: Lift Heavy — Most of the Time

The Importance of High-Intensity Loading

If maximal strength is your goal, you must regularly train with heavy loads. Research defines heavy resistance training as loads greater than 80 percent of one-repetition maximum (1RM). Training in this range has been shown to produce the greatest improvements in maximal force output.

A meta-analysis by Schoenfeld et al. demonstrated that while hypertrophy can occur across a wide range of loads, maximal strength gains are significantly greater when heavier loads are used.

Heavy lifting trains the nervous system to coordinate muscle fibers efficiently, improve firing rates, and synchronize motor unit recruitment. These neural adaptations are essential for expressing high levels of force.

Strength Is a Skill

Strength is not just muscle size. It is a learned motor skill. Heavy lifting teaches the brain how to recruit muscles effectively under high loads.

Research using neural imaging and electromyography shows that heavy resistance training improves corticospinal excitability and reduces inhibitory neural signals. In simple terms, heavy lifting teaches your nervous system to “get out of its own way.”

Light loads rarely provide enough neural stimulus to develop these adaptations, even if sets are taken to failure.

How Heavy Is Heavy Enough?

For most compound lifts, effective strength training occurs between 80 and 95 percent of 1RM, typically for 1 to 6 repetitions per set.

This does not mean training at maximal loads every session. Instead, heavy training should be the backbone of your program, supported by moderate and lighter sessions for volume, technique, and recovery.

Research on undulating and block periodization shows that alternating heavy and moderate intensity sessions produces better strength outcomes than constant high intensity alone.

Safety and Technique Matter

Heavy lifting demands good technique. Studies consistently show that injury risk is more closely related to poor technique, fatigue, and sudden spikes in training load than to heavy weights themselves.

Gradual exposure, proper warm-ups, and maintaining technical standards significantly reduce injury risk while allowing the benefits of heavy training to accumulate.

Tip 3: Build Muscle to Get Stronger

Muscle Size and Strength Are Closely Linked

While neural adaptations play a major role in early strength gains, long-term strength potential is heavily influenced by muscle cross-sectional area. Larger muscles can produce more force.

Multiple longitudinal studies show strong correlations between increases in muscle size and improvements in maximal strength, particularly over longer training periods.

A systematic review by Morton et al. confirmed that hypertrophy contributes significantly to strength development once neural adaptations plateau.

Hypertrophy Expands Your Strength Ceiling

Think of muscle size as the ceiling for strength. Neural efficiency determines how close you get to that ceiling, but muscle mass determines how high the ceiling is.

Athletes who neglect hypertrophy often plateau earlier. Those who intentionally build muscle through adequate volume, nutrition, and recovery can continue gaining strength for years.

Effective Hypertrophy Training for Strength Athletes

Research shows that muscle growth occurs across a wide range of loads, provided sets are taken close to failure and sufficient volume is performed.

Effective hypertrophy parameters include:

• Loads between 60 and 80 percent of 1RM

• Sets of 6 to 15 repetitions

• 10 to 20 hard sets per muscle group per week

Combining hypertrophy-focused accessory work with heavy compound lifts allows you to grow muscle without sacrificing strength specificity.

Why Isolation Exercises Matter

Isolation exercises increase total volume without excessive nervous system fatigue. Studies show that including single-joint movements can enhance muscle growth and joint health when used appropriately.

For strength athletes, isolation work supports weak points, improves muscle balance, and reduces injury risk — all of which contribute to long-term strength gains.

Tip 4: Recover Like Strength Depends on It — Because It Does

Strength Is Built During Recovery, Not Training

Training provides the stimulus, but recovery is where adaptation happens. Without adequate recovery, performance stagnates or declines.

Research consistently shows that insufficient recovery impairs strength gains, increases injury risk, and disrupts hormonal balance.

Sleep Is Non-Negotiable

Sleep is the most powerful recovery tool available. Studies demonstrate that sleep deprivation reduces maximal strength, power output, reaction time, and neuromuscular coordination.

Research by Reilly and Edwards showed that even one night of restricted sleep can significantly impair strength performance.

Sleep also regulates anabolic hormones such as testosterone and growth hormone, both of which play roles in muscle repair and growth.

Aim for 7 to 9 hours of quality sleep per night. Consistency matters more than perfection.

Managing Training Stress

More training is not always better. Excessive volume or intensity without adequate deloads leads to overreaching or overtraining.

Periodized programs that include planned reductions in volume or intensity consistently outperform programs that push maximal effort year-round.

Monitoring subjective fatigue, bar speed, and performance trends helps identify when recovery needs to be prioritized.

Nutrition and Recovery

Adequate energy intake is essential for recovery. Research shows that chronic caloric deficits impair strength gains, even when protein intake is sufficient.

Carbohydrates play a key role in replenishing muscle glycogen, which supports training performance and recovery. Studies show that low glycogen levels reduce force output and increase perceived exertion.

Tip 5: Eat Enough Protein — and Enough Calories

Protein Is Essential for Strength Adaptation

Protein provides the amino acids required for muscle repair and growth. Numerous studies confirm that higher protein intakes support greater strength and hypertrophy when combined with resistance training.

A meta-analysis by Morton et al. found that protein intakes of approximately 1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight per day maximize training-induced gains in lean mass for most individuals.

Distribution Matters

Research suggests that spreading protein intake evenly across meals improves muscle protein synthesis compared to skewed intake patterns.

Consuming 20 to 40 grams of high-quality protein per meal appears to maximize muscle protein synthesis in most adults.

Calories Drive Progress

Strength training is energetically expensive. Chronic under-eating limits recovery and adaptation.

Studies show that individuals in a caloric surplus gain strength and muscle more effectively than those in maintenance or deficit phases, assuming training is consistent.

While it is possible to gain strength while losing fat, progress is typically slower. For maximal strength gains, periods of controlled caloric surplus are highly effective.

Long-Term Nutritional Consistency

Short-term diets rarely support long-term strength. Research on athlete development consistently emphasizes sustainable nutrition strategies over aggressive restriction.

Eating enough, consistently, supports recovery, hormonal health, and training quality — all critical for getting super strong.

Conclusion: Strength Is Built by Boring Excellence

Getting super strong in 2026 will not come from novelty. It will come from doing the fundamentals exceptionally well, week after week.

Progressive overload, heavy lifting, muscle growth, recovery, and nutrition are not optional. They are the biological requirements for strength adaptation.

The science is clear. If you align your training and lifestyle with these principles, your strength will increase — predictably and sustainably.

Bibliography

• Peterson, M.D., Rhea, M.R. and Alvar, B.A. (2004). Applications of the dose-response for muscular strength development: A review of meta-analytic efficacy and reliability for designing training prescription. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 18(2), pp.377–382.

• Schoenfeld, B.J., Grgic, J., Ogborn, D. and Krieger, J.W. (2017). Strength and hypertrophy adaptations between low- vs. high-load resistance training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(12), pp.3508–3523.

• Morton, R.W., Murphy, K.T., McKellar, S.R., Schoenfeld, B.J., Henselmans, M., Helms, E., Aragon, A.A., Devries, M.C. and Phillips, S.M. (2018). A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training–induced gains in muscle mass and strength. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(6), pp.376–384.

• Reilly, T. and Edwards, B. (2007). Altered sleep–wake cycles and physical performance in athletes. Physiology & Behavior, 90(2–3), pp.274–284.

About the Author

Robbie Wild Hudson is the Editor-in-Chief of BOXROX. He grew up in the lake district of Northern England, on a steady diet of weightlifting, trail running and wild swimming. Him and his two brothers hold 4x open water swimming world records, including a 142km swim of the River Eden and a couple of whirlpool crossings inside the Arctic Circle.

He currently trains at Falcon 1 CrossFit and the Roger Gracie Academy in Bratislava.