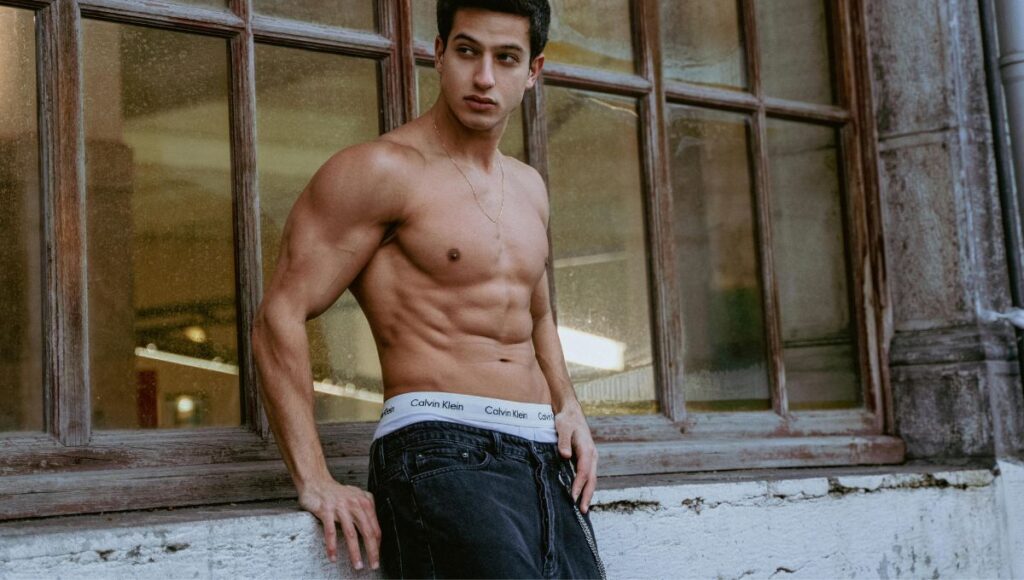

Visible abs and a strong core are two of the most common fitness goals in the world. Yet they are also among the most misunderstood. People do hundreds of crunches, hold endless planks, and chase soreness—only to see little progress. This is not because ab training does not work, but because many people repeat the same mistakes that research has already shown to be ineffective.

Your abdominal muscles are skeletal muscles like any other. They respond to progressive overload, appropriate volume, sufficient recovery, and intelligent exercise selection. When these principles are ignored, time and effort are wasted.

This article breaks down seven of the most common ab training mistakes, explains why they fail using scientific evidence, and shows how to fix them. The goal is not to train abs harder, but smarter.

Mistake 1: Believing Abs Are Built With High Reps and Light Effort

Why This Mistake Is So Common

Many people assume abs are different from other muscles. Because the abs are involved in posture and breathing, they are often treated as endurance muscles that should be trained with very high repetitions and little resistance. This belief has led to workouts built around sets of 50 to 100 crunches or endless circuits with no added load.

What Science Actually Says

The abdominal muscles, including the rectus abdominis, external obliques, and internal obliques, are composed of a mix of slow-twitch and fast-twitch muscle fibers. Research using muscle biopsy data shows that the rectus abdominis contains a substantial proportion of type II fibers, similar to many limb muscles (Johnson et al., 1973). This means the abs are capable of strength and hypertrophy adaptations, not just endurance.

Studies on resistance training consistently show that muscle growth is driven by mechanical tension and progressive overload rather than repetition count alone (Schoenfeld, 2010). When load is too light, mechanical tension is insufficient to stimulate maximal hypertrophy.

Electromyography (EMG) research has also shown that adding resistance to abdominal exercises significantly increases muscle activation compared to bodyweight-only movements (Escamilla et al., 2010).

Why High-Repetition Ab Training Wastes Time

High-rep ab training primarily improves muscular endurance. While endurance has value, it does little to increase muscle thickness or strength once basic conditioning is achieved. Performing hundreds of reps may burn calories, but it does not challenge the abs enough to grow or get stronger.

How to Fix It

Train abs the same way you train other muscles:

- Use added resistance such as cables, weights, or bands.

- Keep most sets in the 6–15 rep range.

- Progress load over time.

Exercises like weighted cable crunches, decline sit-ups with load, and hanging leg raises with ankle weights are far more effective than endless crunches.

Mistake 2: Chasing a “Six-Pack Burn” Instead of Mechanical Tension

The Appeal of the Burn

The burning sensation in the abs is often seen as proof of an effective workout. This feeling comes from metabolite accumulation, particularly hydrogen ions produced during glycolysis. Many ab routines are designed specifically to create this burn.

What the Burn Does—and Does Not—Mean

While metabolic stress can contribute to hypertrophy, it is not the primary driver. Mechanical tension remains the most important stimulus for muscle growth (Schoenfeld, 2010). The burn is not a reliable indicator of muscle activation, strength gains, or hypertrophy.

EMG studies have demonstrated that exercises that produce a strong burn do not always produce high levels of muscle activation (Escamilla et al., 2006). Conversely, heavy anti-extension and anti-rotation exercises may not produce much burn but place significant tension on the abdominal muscles.

Why Burn-Based Training Falls Short

Burn-focused training often relies on short rest periods and low resistance. This limits force production and reduces the ability to overload the muscle. Over time, adaptation plateaus because the stimulus does not increase.

How to Fix It

Prioritize exercises that:

- Require high force production.

- Challenge spinal stability under load.

- Allow progression.

Examples include heavy ab rollouts, loaded carries, Pallof presses, and weighted leg raises. These exercises create high mechanical tension even if the burn is minimal.

Mistake 3: Isolating Abs While Ignoring the Core’s True Function

The Misunderstanding of “Core Training”

Many people equate core training with spinal flexion exercises like crunches and sit-ups. While these movements target the rectus abdominis, they ignore the primary role of the core in real-world movement.

What the Core Is Designed to Do

The core’s main function is to stabilize the spine and transfer force between the upper and lower body. This includes resisting:

- Extension

- Rotation

- Lateral flexion

Biomechanical research shows that excessive spinal flexion under load can increase disc stress and injury risk, especially when performed repeatedly (McGill, 2007).

Why Crunch-Only Training Is Incomplete

Focusing solely on spinal flexion underemphasizes the obliques, transverse abdominis, and deep stabilizers. It also fails to improve functional strength that carries over to sports, lifting, and daily movement.

Studies have found that anti-movement exercises like planks and rollouts produce comparable or greater abdominal activation than crunches while placing less stress on the spine (Ekstrom et al., 2007).

How to Fix It

Include exercises that train the core as a stabilizer:

- Anti-extension: ab rollouts, dead bugs

- Anti-rotation: Pallof presses, cable chops

- Anti-lateral flexion: suitcase carries, side planks

These movements build strength that transfers to performance and reduces injury risk.

Mistake 4: Doing Ab Work Every Day Without Recovery

Why People Overtrain Abs

Because ab workouts often feel less taxing than heavy squats or deadlifts, many people assume they can be trained daily without consequences. Abs are often added at the end of every session.

What Research Shows About Recovery

Muscle protein synthesis after resistance training remains elevated for 24 to 48 hours depending on training volume and intensity (Damas et al., 2015). Training the same muscle group intensely every day can interfere with recovery and adaptation.

There is no evidence that abdominal muscles recover faster than other skeletal muscles when trained with sufficient load. Like any muscle, they require recovery to grow stronger.

Why Daily Ab Training Can Stall Progress

Without recovery, cumulative fatigue increases and performance declines. This leads to reduced force output and less effective training sessions. Over time, progress slows or stops entirely.

How to Fix It

Treat abs like any other muscle group:

- Train them 2–4 times per week.

- Allow at least 48 hours between hard sessions.

- Adjust volume based on overall training load.

Quality sessions with recovery outperform daily low-quality work.

Mistake 5: Expecting Ab Exercises to Reveal Abs Without Fat Loss

The Persistent Spot Reduction Myth

One of the most damaging myths in fitness is that training a muscle burns fat from that area. This belief is especially common with abs.

What Science Says About Fat Loss

Multiple studies have demonstrated that localized fat loss through targeted exercise does not occur. Fat loss is systemic and driven by overall energy balance (Katch et al., 1984; Kostek et al., 2007).

Even intense ab training does not significantly reduce abdominal subcutaneous fat unless total body fat decreases.

Why Ab Work Alone Does Not Reveal Abs

Visible abs require low enough body fat levels for muscle definition to show. No amount of crunches can overcome a calorie surplus or poor dietary habits.

How to Fix It

Understand the division of labor:

- Ab training builds muscle thickness and strength.

- Nutrition and overall training drive fat loss.

A calorie-controlled diet combined with resistance training and sufficient protein intake is essential for revealing abs (Phillips and Van Loon, 2011).

Mistake 6: Using Poor Technique and Excessive Momentum

How Technique Breaks Down

Many ab exercises are performed with excessive hip flexor involvement, momentum, or spinal movement that shifts load away from the abs. Common examples include swinging leg raises and jerking sit-ups.

Why This Reduces Effectiveness

EMG research shows that improper technique dramatically reduces abdominal activation while increasing hip flexor contribution (Juker et al., 1998). This not only limits ab development but can also increase lumbar spine stress.

The Injury Risk Factor

Repeated spinal flexion combined with momentum increases shear forces on the lumbar spine. Over time, this may contribute to disc degeneration and low back pain (McGill, 2007).

How to Fix It

Focus on:

- Controlled tempo

- Posterior pelvic tilt during flexion exercises

- Minimal momentum

Quality repetitions produce better results than higher rep counts with poor form.

Mistake 7: Ignoring Progressive Overload for the Abs

Why Abs Often Stop Improving

Many people use the same ab routine for months or years. When the stimulus does not increase, the body has no reason to adapt.

What Progressive Overload Means for Abs

Progressive overload does not require adding weight every session. It can include:

- Increasing resistance

- Increasing range of motion

- Improving leverage

- Increasing time under tension

Research consistently shows that progressive overload is essential for long-term strength and hypertrophy gains (Kraemer and Ratamess, 2004).

Why Static Ab Routines Fail

Once an exercise becomes easy, muscle activation decreases and adaptation slows. This leads to stagnation despite consistent effort.

How to Fix It

Track ab training like any other lift:

- Log sets, reps, and load.

- Progress difficulty gradually.

- Rotate exercises strategically.

Treating abs seriously produces serious results.

Final Thoughts

Ab training is simple, but it is not easy. The biggest waste of time comes from treating abs as special muscles that break the rules of physiology. They do not. When trained with appropriate load, intelligent exercise selection, sufficient recovery, and realistic expectations about fat loss, the abs respond just like any other muscle group.

Stop chasing burns, shortcuts, and myths. Start training abs with the same respect you give the rest of your body.

References

- Damas, F., Phillips, S.M., Lixandrão, M.E., Vechin, F.C., Libardi, C.A., Roschel, H. and Tricoli, V. (2015). Resistance training-induced changes in integrated myofibrillar protein synthesis are related to hypertrophy only after attenuation of muscle damage. Journal of Physiology, 594(18), pp.5209–5222.

- Ekstrom, R.A., Donatelli, R.A. and Carp, K.C. (2007). Electromyographic analysis of core trunk, hip, and thigh muscles during nine rehabilitation exercises. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 37(12), pp.754–762.

- Escamilla, R.F., McTaggart, M.S., Fricklas, E.J., DeWitt, R., Kelleher, P., Taylor, M.K., Hreljac, A. and Moorman, C.T. (2006). An electromyographic analysis of commercial and common abdominal exercises. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 36(2), pp.45–57.

About the Author

Robbie Wild Hudson is the Editor-in-Chief of BOXROX. He grew up in the lake district of Northern England, on a steady diet of weightlifting, trail running and wild swimming. Him and his two brothers hold 4x open water swimming world records, including a 142km swim of the River Eden and a couple of whirlpool crossings inside the Arctic Circle.

He currently trains at Falcon 1 CrossFit and the Roger Gracie Academy in Bratislava.