Maintaining a strong, functional core becomes increasingly important after 40. As the body ages, muscle mass naturally declines, metabolism slows, and hormonal changes affect how fat is stored and how efficiently we recover from exercise. A well-designed abdominal training routine can counter many of these effects—but only if approached intelligently, with scientific precision.

This article breaks down eight evidence-based strategies to help adults over 40 strengthen their abs safely and effectively, improving not just appearance but also performance, posture, and long-term health.

1. Prioritize Core Function Over Aesthetics

After 40, the primary goal of ab training should shift from chasing visible six-packs to optimizing function and stability. The core is not just one muscle—it’s a complex system involving the rectus abdominis, obliques, transverse abdominis, diaphragm, pelvic floor, and spinal stabilizers. These muscles work together to transfer force, protect the spine, and maintain efficient movement.

Research shows that a weak or imbalanced core increases the risk of back pain and injuries, especially in adults over 40, when degenerative spinal changes begin to accelerate (Hodges & Richardson, 1996). Functional core exercises—such as planks, dead bugs, and bird dogs—have been shown to activate the deep stabilizing muscles of the abdomen and improve lumbar spine control without excessive spinal loading (McGill, 2010).

Practical Application

Replace endless crunches with exercises that train core stability and coordination. Include movements that challenge anti-extension (planks), anti-rotation (Pallof presses), and anti-lateral flexion (side planks or suitcase carries).

2. Address Age-Related Muscle Loss (Sarcopenia)

Starting around age 40, adults lose 3–8% of muscle mass per decade, a process known as sarcopenia (Volpi et al., 2004). This loss affects all major muscle groups, including the core, reducing strength, balance, and metabolic rate. Counteracting this decline requires two strategies: progressive resistance training and adequate protein intake.

Progressive Overload

To maintain or build abdominal strength, the muscles must be progressively challenged. A 2020 meta-analysis found that resistance training at moderate to high intensity significantly combats age-related muscle loss (Csapo & Alegre, 2016). In the context of ab training, this means gradually increasing difficulty by extending plank times, adding resistance (e.g., cable crunches), or using stability tools like Swiss balls.

Protein and Recovery

Adequate protein intake—around 1.6–2.2 g/kg of body weight per day—supports muscle protein synthesis (Morton et al., 2018). Older adults exhibit anabolic resistance, meaning they need a slightly higher protein dose per meal to trigger the same muscle-building response as younger individuals.

3. Focus on Movement Quality and Motor Control

Aging can impair motor control and proprioception, increasing the risk of poor movement patterns that can strain the lower back or hips during ab training. Studies show that targeted neuromuscular training improves coordination and spinal control, especially in older adults (Granacher et al., 2013).

Practical Application

Slow down your movements. Focus on controlled eccentric phases and proper breathing. Exercises like the dead bug or slow mountain climber encourage precision over speed, reinforcing correct muscle activation patterns and reducing compensations.

Breathing Mechanics

Many people neglect the diaphragm’s role in core function. Diaphragmatic breathing increases intra-abdominal pressure, stabilizing the spine and improving performance during ab exercises (Hodges et al., 2005). Practice exhaling fully during exertion and inhaling through the diaphragm during recovery.

4. Incorporate Anti-Extension and Anti-Rotation Training

As we age, spinal mobility decreases while stiffness increases, making dynamic flexion exercises like sit-ups less safe and effective. Instead, stability-based training improves strength and reduces injury risk.

Anti-Extension

Anti-extension exercises resist arching of the lower back and train the deep core stabilizers. The front plank and ab wheel rollout are effective examples. A 2017 study demonstrated that isometric anti-extension exercises recruit more of the transverse abdominis and internal obliques than dynamic flexion-based movements (Escamilla et al., 2017).

Anti-Rotation

Rotational control is key for spine safety and athletic performance. Exercises like the Pallof press and half-kneeling chop improve the body’s ability to resist unwanted movement, which is critical for adults with lower back vulnerability (Behm et al., 2010).

5. Train for Stability Before Power

Before pursuing advanced core exercises or rotational power drills, older adults should establish baseline stability. Attempting to generate force without proper control increases injury risk, particularly in the lumbar spine and hip complex.

The McGill Big Three

Renowned spine researcher Stuart McGill advocates three core stability exercises: the modified curl-up, side plank, and bird dog. These moves enhance endurance and spine stability with minimal compressive load (McGill, 2010).

Progression Strategy

Once stability is established, add controlled dynamic movements like medicine ball slams or rotational cable chops to build power safely. Research supports power training for maintaining neuromuscular performance in older adults (Reid & Fielding, 2012), but only when built upon a foundation of stability.

6. Include Multi-Planar and Compound Movements

Real-life core function occurs across multiple planes of motion—sagittal, frontal, and transverse. Training the abs in isolation overlooks how the core stabilizes during full-body movements.

Multi-Planar Training

Movements like the single-arm farmer’s carry or rotational lunges engage the core across all planes. These exercises also improve balance and proprioception, both of which decline with age (Granacher et al., 2013).

Compound Integration

Strength exercises like deadlifts, squats, and overhead presses activate the core dynamically to stabilize the spine. Studies show that compound lifts stimulate significant core activation comparable to isolated ab exercises (Aspe & Swinton, 2014). For adults over 40, this integration improves strength efficiency and reduces training volume demands.

7. Prioritize Mobility and Postural Alignment

A common mistake among older trainees is focusing on ab strength while neglecting mobility and posture. Thoracic immobility, tight hip flexors, and weak glutes can all compromise ab training effectiveness and increase lower back stress.

Hip and Thoracic Mobility

Age-related stiffness in the hips and spine restricts movement efficiency. Incorporating dynamic stretches such as the world’s greatest stretch, 90/90 hip rotations, and thoracic openers can restore range of motion (Behm & Chaouachi, 2011).

Postural Reset

Forward head posture and rounded shoulders are prevalent in adults who sit for long hours. This posture lengthens the abdominals and inhibits their function. Integrating postural corrective exercises—such as wall slides, band pull-aparts, and glute bridges—enhances the effectiveness of ab workouts by aligning the body’s kinetic chain.

8. Manage Recovery, Stress, and Hormones

Training intensity must match recovery capacity, which naturally declines with age. Adults over 40 experience reduced anabolic hormone levels, slower tissue repair, and heightened inflammation, all of which affect core training results.

Recovery Strategies

Studies indicate that older adults benefit from longer recovery periods between intense sessions—48–72 hours per muscle group (Kraemer & Ratamess, 2005). Incorporating low-impact activities like walking, yoga, or mobility flow on off days enhances blood flow and aids recovery.

Sleep and Stress

Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which promotes abdominal fat storage and hinders muscle repair (Hackney, 2006). Adequate sleep—at least 7 hours per night—supports hormonal balance and recovery, with evidence linking sleep quality to improved muscle protein synthesis (Dattilo et al., 2011).

Sample Weekly Core Routine for Adults Over 40

Day 1: Stability and Control

- Dead Bug: 3×10 per side

- Bird Dog: 3×10 per side

- Front Plank: 3×30–60 seconds

- Pallof Press: 3×12

Day 2: Strength Integration

- Single-Arm Farmer’s Carry: 3×40 meters

- Side Plank: 3×30–45 seconds per side

- Cable Chop: 3×10 per side

- Glute Bridge March: 3×15

Day 3: Mobility and Power

- Thoracic Rotation Stretch: 3×10 per side

- Medicine Ball Slam: 3×8

- Rotational Lunge: 3×10 per side

- Anti-Rotation Hold: 3×20 seconds per side

This structure emphasizes stability first, then strength and mobility, aligning with physiological needs and evidence-based best practices for adults over 40.

Conclusion

Training the abs after 40 requires a strategic shift from volume and aesthetics to function, control, and recovery. By prioritizing stability, integrating compound movements, and respecting recovery cycles, adults can maintain a strong, pain-free, and functional core well into later life.

Every rep should serve the goal of building resilience—not just definition.

Key Takeaways

| Principle | Explanation | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Focus on Function | Core stability and coordination matter more than appearance. | Hodges & Richardson (1996), McGill (2010) |

| Combat Sarcopenia | Progressive resistance and high protein intake preserve muscle. | Volpi et al. (2004), Csapo & Alegre (2016) |

| Prioritize Control | Slower, precise movement prevents injury. | Granacher et al. (2013) |

| Use Anti-Movement Drills | Planks and Pallof presses enhance spinal stability. | Escamilla et al. (2017), Behm et al. (2010) |

| Build Stability First | Foundation before power reduces spinal risk. | McGill (2010), Reid & Fielding (2012) |

| Train Multi-Planar | Real-world movement requires 3D core engagement. | Aspe & Swinton (2014) |

| Improve Mobility | Hip and thoracic flexibility enhance performance. | Behm & Chaouachi (2011) |

| Respect Recovery | Hormonal and stress balance aid muscle retention. | Kraemer & Ratamess (2005), Hackney (2006) |

References

- Aspe, R.R. & Swinton, P.A. (2014). Electromyographic and kinetic comparison of the back squat and overhead squat. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(10), 2827–2836.

- Behm, D.G. & Chaouachi, A. (2011). A review of the acute effects of static and dynamic stretching on performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 111(11), 2633–2651.

- Behm, D.G., Drinkwater, E.J., Willardson, J.M., & Cowley, P.M. (2010). Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology position stand: stability ball training. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 35(1), 109–120.

- Csapo, R. & Alegre, L.M. (2016). Effects of resistance training with moderate vs heavy loads on muscle mass and strength in the elderly. Ageing Research Reviews, 31, 66–78.

- Dattilo, M. et al. (2011). Sleep and muscle recovery: endocrinological and molecular basis. Sleep Science, 4(2), 45–51.

- Escamilla, R.F. et al. (2017). Core muscle activation during Swiss ball and traditional abdominal exercises. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 47(3), 187–195.

- Granacher, U. et al. (2013). Effects of core stability training on dynamic balance in seniors: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 27(4), 1103–1111.

- Hackney, A.C. (2006). Stress and the neuroendocrine system: the role of exercise as a stressor and modifier of stress. Expert Review of Endocrinology & Metabolism, 1(6), 783–792.

- Hodges, P.W. & Richardson, C.A. (1996). Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain: a motor control evaluation. Spine, 21(22), 2640–2650.

- Hodges, P.W., Butler, J.E., McKenzie, D.K., & Gandevia, S.C. (2005). Contraction of the human diaphragm during rapid postural adjustments. Journal of Physiology, 536(1), 243–252.

- Kraemer, W.J. & Ratamess, N.A. (2005). Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training. Sports Medicine, 35(4), 339–361.

- McGill, S.M. (2010). Core training: evidence translating to better performance and injury prevention. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 32(3), 33–46.

- Morton, R.W. et al. (2018). A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training–induced gains. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(6), 376–384.

- Reid, K.F. & Fielding, R.A. (2012). Skeletal muscle power: a critical determinant of physical functioning in older adults. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 40(1), 4–12.

- Volpi, E., Nazemi, R., & Fujita, S. (2004). Muscle tissue changes with aging. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 7(4), 405–410.

image sources

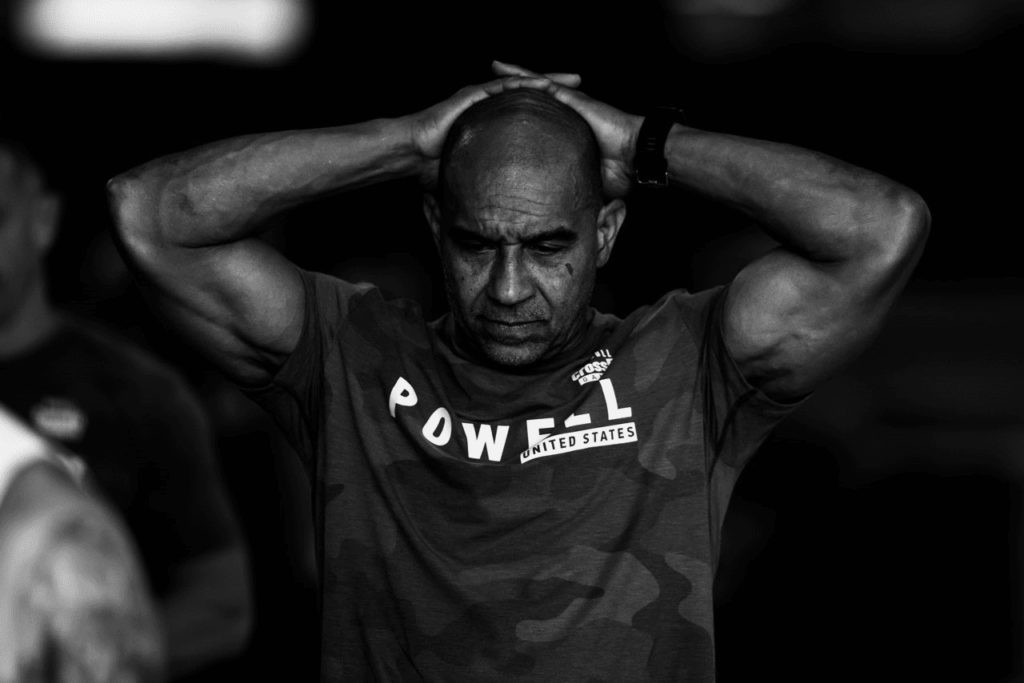

- powell masters athlete: Photo courtesy of CrossFit Inc.