The story of genetics in sport has changed significantly in the last 100 years. The growth in sports participation coupled with the increase in viewership of elite sport has led to a much more challenging route to the top level of sport.

In this age of hypercompetitive sport, it has become increasingly hard to become an elite sports(wo)man. Not only do athletes need to optimise all fields of their training, including routines, mindset, coaches and environments, but they also have to account for their genetics and its role on their sport of choice.

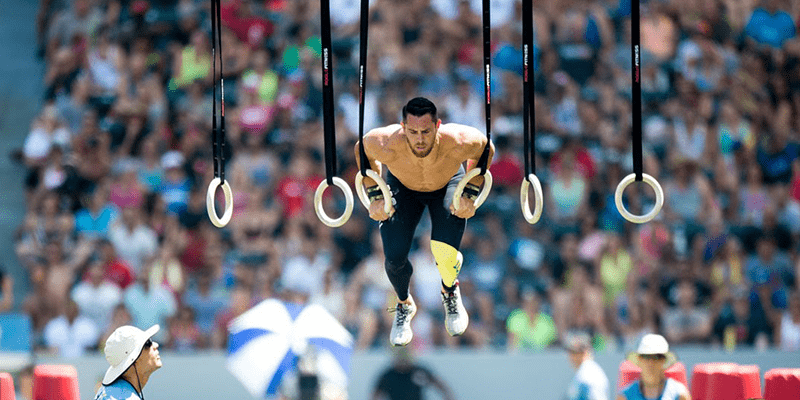

To become an elite athlete, the optimum in each category is some extreme version of it; for example, to qualify to the CrossFit Games an athlete’s mindset must be extremely hardworking, their training environment better than optimal and work ethic spotless.

For the most part the same is true with an athlete’s genetics: most sports favour an extreme genetic makeup of some kind.

“Current evidence suggests that a favorable genetic profile, when combined with the appropriate training, is advantageous, if not critical for the achievement of elite athletic status,” a study titled Genetic influence on athletic performance concluded.

[box]

WHAT IS GENETICS?

Genetics is the study of heredity; the expression of traits and how they’re passed from generation to generation.

It helps us understand the biological programming of all life forms and help explain what makes a person unique, why family members look alike and why some traits run within families.

In the world of sport, it’s widely acknowledged that genetic factors undoubtedly contribute to athletic performance, with certain genetic variations associated with physical performance.

However, one must keep in mind that many genes work in combination and other elements (such as environment or nutrition) also contribute to athletic ability.

A “favourable” genetic profile is only relevant at the elite level of sport, where every athlete has already optimised every other area within their control and little ‘edges’ can be the difference between success and failure.

[/box]

One obvious example of this is the height of basketball players. In order to compete at the top level of basketball, athletes should be exceptionally tall. However, there are a plethora of examples across the world of sport that are not so obvious:

- Waterpolo players benefit from having long forearms (in relation to their total arm length) to help them throw forcefully

- A long torso and short legs will give swimmers a huge advantage

- Conversely, a short torso and long legs helps long distance runners run efficiently

- A predisposition to fast twitch muscle fibres (over slow twitch fibres) will help a sprinter reach fast running speeds

- Rowers tend to be very tall

There are notable differences in body morphology (e.g. body height and composition) between athletes of different specialities, with different body types naturally suited to specific sports. “Highly specialised bodies that fit into certain athletic niches,” as described by investigative reporter David Epstein on his TED talk Are athletes really getting faster, better, stronger? Some people have very specific adaptations that have allowed them to get to the top of the sport.

It’s important to note that specific genetic traits often provide an advantage to those who have the trait, rather than being a requirement to compete at a top level.

The genetic ‘edges’ to be competitive on the elite CrossFit scene are not nearly as extreme as the above examples; you do not need to be particularly tall, have a large arm span, or be a “genetic freak” to qualify for the CrossFit Games.

This is highlighted by the fact that, looking at the available data, the average height of the top 20 finishers in the CrossFit Games across the last 5 years is no different to the average height of the general population in the countries these athletes are from.

For example, the average height of the top 20 male CrossFit Games finishers in the last five years is 5’9.7”, while the average height of US males between the ages of 18 and 35 (the same age range of individual Games competitors) is 5’9.4”.

There are incredibly few CrossFit athletes that are very tall of very short; there’s only one Brent Fikowski and only one Josh Bridges, almost all the other athletes are of average height.

The same holds true for female athletes. On average, the top 20 female CrossFit Games athletes are 5’4.9” and the US population for women between 18 and 35-years-old is 5’4.1”.

When assessing if an athlete might make it to the elite level, a basketball coach can simply get his tape measure out – a CrossFit coach can’t do this.

[box]

GENETIC TRAITS FAVOURABLE FOR SPORTS

The most studied genes associated the most with sports performance are ACE I/D and ACTN3 R577X – these gene variants have constantly been associated with endurance and power related performance, although, according to a University of Maryland study, neither can be considered predictive.

This means that, even if a person expresses these gene variants, that alone will not determine or secure their path to elite athleticism.

Nevertheless, it’s important to accept that certain genetic traits might mean the difference between an Olympic champion and an Olympic athlete. It’s believed that, when two athletes follow the same training, are influenced by the same environmental factors, etc. one of them one of them will surpass the other because of his genetics.

“[…]although deliberate training and other environmental factors are critical for elite performance, they cannot by themselves produce an elite athlete. Rather, individual performance thresholds are determined by our genetic make-up,” a 2012 study in the British Journal of Sport Medicine found.

“Elite sporting performance is the result of the interaction between genetic and training factors,” it concluded.

[/box]

Of course there are certain genetic traits needed in order to compete at an elite level in most sports, including CrossFit. How strongly your body reacts to training will be, in part, dictated by your genetic code. Some people have genes that will allow them to recover from training much faster than others, which means they can put in hard training sessions more often and progress faster.

Nevertheless, these hidden genetics are often influenced by other factors. Getting adequate sleep, for example, is critical to effective recovery.

Contrary to popular opinion, bodybuilder Dorian Yates is a great example of someone who’s genetics, albeit hidden genetics, allowed him to be exceptional in his sport.

Yates dominated the bodybuilding scene for years, winning six consecutive Mr Olympia titles from 1992 to 1997. He’s widely considered to be one of the top bodybuilders in modern history.

Although Yates was not particularly muscular without training, he responded very well to training once he started, building muscle very fast and recovering from training sessions at extraordinary speed. Coupled with his amazing work ethic this meant he was able to reach the top level in bodybuilding very fast.

This is not something most people could expect to copy, regardless of how hard they train. Most people would simply pick up injuries or succumb to overtraining if they attempted to increase their training load like Yates did.

[box]

GENETICS IS NOT ONLY ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS

Your nurture affects your nature directly. A person inherits a complete set of genes from each parent, as well as a vast array of cultural and socioeconomic experiences from his/her family.

Genes interact with each other in ways not yet fully understood, which means even with the “right” genotype to become an Olympic champion, the way these genes are expressed (phenotype) varies and depends on nurture.

Genotype is a collection of genes, the actual genetic sequence of base pairs. Phenotype is the sum of an individual’s observable characteristics, the way your genotype is expressed resulting from its interaction with the environment.

For example, an individual’s genotype might predispose them to being tall. However, if that individual is malnourished as a child. They might not be as tall as the same genetic makeup could have allowed them had they received better nutrition.

However, this hypothetical malnourished individual will still be taller than somebody who experiences the same (mal)nutrition as a child but has genes that predispose them to being smaller.

What this means in a sporting context is that your genes guide you somewhere, but they don’t force you, as environmental factors play a big role in your athletic performance.

[/box]

As much as an individual’s reaction to training (determined partly by genetics) will have an effect on their performance, genetics isn’t the only answer to the top. How hard an athlete trains has a huge influence on their results. In order to make the most of genetic ‘edges’ and become the best, an athlete’s ought to put more time and effort than anyone else.

There are a wide range of hidden genetics at play within CrossFit and some of this genetics is more hidden than others. Firstly, there’s the genetics that is hard to measure, such as how fast an athlete will recover from a hard training session. Then, there is genetics that’s difficult to notice, but easily measurable.

For example, researchers have recently started looking into hand size in judo, where hand grip plays a major role, theorising that larger hands could be useful when competing. If this turns out to be the case, then it is something easily measurable, but in all the years of judo being contested at a high level has not been noticed until now.

In a sport like CrossFit, where workouts are naturally varied, the diversity in elite CrossFit athlete’s bodies is higher than many other sports. So, while rowing generally favours the tall, it’s beneficial to be small in gymnastics. The fact that CrossFit workouts include both rowing and gymnastics, sometimes within moments of each other, allows all genetic types to excel at different points.

CrossFit is not a sport that requires highly specific or extreme genetics in order to be competitive – and if it does, the useful genetics is well hidden.

In fact, this is the very foundation of CrossFit. Gregg Glassman founded the sport after noticing he could be quite good at many disciplines without excelling at a single one; that’s when the “jack of all trades, master of none” ethos of the sport was born. One could argue this came about in part because Glassman is not a genetic outlier. Had he found success in a single sport he might have taken a different route.

While the sport is funded in variety, its participants aren’t quite there yet. The barrier to participation to CrossFit is relatively high, and in past years the sport has been condemned for being “unwelcoming to people of colour” and reserved for the wealthy.

Racial diversity and the diverse genetic makeup that comes with it really only entered the competitive field of CrossFit last year, with a female and male athlete of every country qualifying to compete at the CrossFit Games, and even this was only short-lived.

If there are specific genetic traits that are beneficial for CrossFit, these might not have entered the competitive genetic pool yet. Genetics only matters if the competitive field mirrors this.

What that means is that the competitive filed determines if genetics can give someone a competitive advantage; the bigger the competition, the more important the ‘edges’ become. At the same time, a larger and more diverse genetic pool would mean advantageous traits become obvious.

Ultimately, CrossFit’s program, in its methodologies and implementation, aims to physically prepare trainees “not only for the unknown but for the unknowable as well.”

The methodology flows all the way to the CrossFit Games, where athletes only learn the competition’s workouts days, hours or minutes before taking onto the competition floor. Because of the mystery and uniqueness of the tests, on an elite level, certain genetic traits might be beneficial in different years, depending on the programming.

Considering the number of body systems that must interact (musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, respiratory, nervous, etc.), athletic performance is one of the most complex human traits. Combined with other important elements that also contribute to athletic ability (for example environment or nutrition), one cannot attribute an athlete’s success or failure to genetics alone.

And, while certain genetic traits might give athletes an edge over others while training, it seems like there aren’t any highly specific or extreme genetics at play for elite CrossFit athletes.

image sources

- genetics-in-crossfit-brent: BOXROX