Protein is an essential macronutrient for muscle repair, growth, and overall health. While meat is a traditional source of protein, concerns around sustainability, cost, and health have led many to explore alternative ways to maintain high protein intake whilst eating less meat.

This article provides evidence-based guidance on how to achieve a high-protein diet with reduced reliance on meat, highlighting plant-based protein sources, dietary planning, and practical meal strategies.

Why Protein Matters

Protein is vital for numerous physiological functions, including muscle synthesis, immune health, and the production of enzymes and hormones (Phillips & Van Loon, 2011). For individuals engaging in physical activity or strength training, consuming adequate protein supports muscle recovery and hypertrophy.

Research recommends a daily intake of 1.6–2.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight for athletes and active individuals (Morton et al., 2018).

Challenges of Reducing Meat Intake

Reducing meat consumption poses challenges, as meat provides a complete amino acid profile and is a dense protein source. Plant-based proteins often lack one or more essential amino acids, requiring strategic combinations to ensure adequate intake. Additionally, non-meat protein sources may have lower digestibility due to anti-nutritional factors like phytates in legumes (FAO, 2013).

Strategies to Maintain High Protein Intake

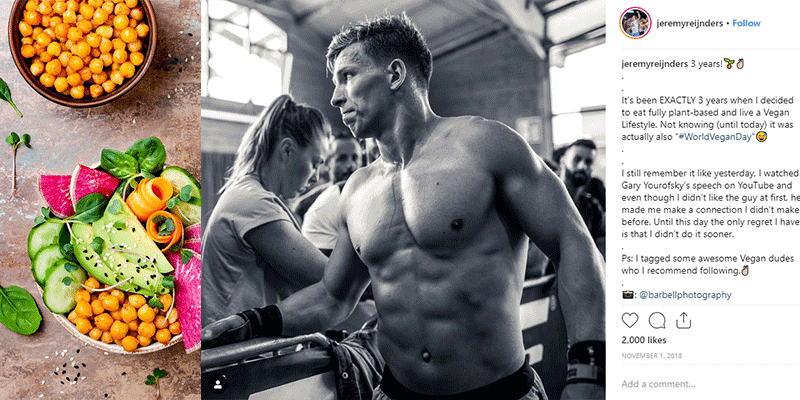

1. Incorporate Legumes as Protein Staples

Legumes such as lentils, chickpeas, and black beans are excellent sources of plant protein. A cup of cooked lentils provides approximately 18 grams of protein (USDA, 2021). Combining legumes with whole grains like quinoa or brown rice creates a complete protein by providing all essential amino acids.

Supporting Evidence

Studies show that diets rich in legumes can effectively meet protein requirements while reducing saturated fat and cholesterol intake, promoting cardiovascular health (Bazzano et al., 2001).

2. Optimise Protein from Whole Grains

Whole grains like quinoa, farro, and bulgur contain higher protein content than refined grains. Quinoa, for example, contains 8 grams of protein per cup and is a complete protein source (USDA, 2021).

Practical Tips

Use quinoa as a base for salads or as a replacement for rice in meals. Pairing grains with legumes maximises the amino acid profile, ensuring high-quality protein intake.

3. Add High-Protein Vegetables

Certain vegetables, such as spinach, broccoli, and peas, provide moderate amounts of protein alongside essential micronutrients. For instance, 1 cup of cooked spinach contains around 5 grams of protein (USDA, 2021). Including a variety of high-protein vegetables in meals can contribute significantly to daily protein goals.

4. Explore Dairy and Eggs

Dairy products and eggs are rich in protein and provide essential nutrients like calcium and vitamin D. Greek yoghurt, cottage cheese, and eggs are particularly high in protein. For example, a single large egg contains 6 grams of protein, while a cup of Greek yoghurt provides 20 grams (USDA, 2021).

Supporting Evidence

Research highlights that dairy proteins, particularly whey, have high biological value and support muscle protein synthesis effectively (Tang et al., 2009).

5. Use Plant-Based Protein Powders

Plant-based protein powders derived from sources like pea, rice, or hemp are convenient for supplementing protein intake. A single scoop of pea protein powder provides around 20 grams of protein. These powders are particularly useful for individuals with higher protein requirements.

Considerations

Ensure the selected protein powder is free from additives and sweeteners. Combining plant protein powders (e.g., pea and rice) enhances amino acid completeness.

6. Include Protein-Rich Snacks

Snacking on high-protein foods can bridge gaps in daily intake. Options include roasted chickpeas, edamame, or hummus with whole-grain crackers. These snacks are not only high in protein but also provide fibre and healthy fats.

Research Insight

Edamame (soybeans) offers a complete protein profile and contains 18 grams of protein per cup (USDA, 2021). Including soy-based snacks has been shown to lower cholesterol and improve heart health (Anderson et al., 1995).

7. Experiment with Meat Substitutes

Meat substitutes like tofu, tempeh, and seitan are protein-rich and versatile in cooking. Seitan, made from wheat gluten, provides a whopping 21 grams of protein per 100 grams (USDA, 2021).

Cooking Tips

Marinate tofu or tempeh to improve flavour and texture. Use seitan in stir-fries, stews, or sandwiches as a meat substitute.

8. Fortify Meals with Nuts and Seeds

Nuts and seeds, such as almonds, chia seeds, and sunflower seeds, contribute additional protein. Two tablespoons of chia seeds contain 5 grams of protein and can be added to smoothies, oatmeal, or yoghurt.

Health Benefits

Besides protein, nuts and seeds are rich in omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants, supporting overall health (Ros, 2010).

9. Plan Meals Strategically

Achieving a high-protein diet with less meat requires thoughtful meal planning. Focus on creating meals with multiple plant-based protein sources to ensure amino acid completeness.

Sample High-Protein Meat-Less Meal

- Quinoa and lentil salad with roasted vegetables and tahini dressing.

- Greek yoghurt with chia seeds and fresh berries for dessert.

10. Leverage Fermented Foods

Fermented foods like miso, tempeh, and natto not only provide protein but also support gut health. Tempeh, for example, contains 19 grams of protein per 100 grams (USDA, 2021).

Supporting Evidence

Fermentation enhances protein digestibility and reduces anti-nutritional factors, making plant proteins more bioavailable (Frias et al., 2008).

Additional Considerations

Addressing Protein Digestibility

Plant proteins often have lower digestibility compared to animal proteins. Cooking, fermenting, and sprouting legumes and grains improve their digestibility and nutrient absorption (Millward, 1999).

Balancing Macronutrients

While focusing on protein, ensure the diet includes sufficient carbohydrates and fats for energy and overall nutritional balance. Whole foods such as sweet potatoes, avocados, and olive oil complement a high-protein, meat-reduced diet.

Conclusion

Reducing meat consumption does not mean compromising protein intake. By incorporating a variety of plant-based sources, optimising meal combinations, and leveraging supplements where necessary, it is entirely feasible to maintain high protein intake. This approach benefits not only personal health but also aligns with environmental sustainability goals.

Key Takeaways

| Key Point | Summary |

|---|---|

| Focus on legumes and whole grains | Combine these to create complete proteins and ensure amino acid balance. |

| Incorporate high-protein vegetables | Add options like spinach, broccoli, and peas to meals. |

| Utilise dairy and eggs | Include Greek yoghurt, cottage cheese, and eggs for high biological value. |

| Use plant-based protein powders | Supplement with powders like pea and rice for convenience. |

| Explore meat substitutes | Include tofu, tempeh, and seitan for versatile, protein-rich options. |

| Add nuts, seeds, and snacks | Include chia seeds, almonds, and roasted chickpeas as nutrient-dense snacks. |

| Plan meals strategically | Combine multiple sources to maximise protein and nutrient intake. |

Bibliography

Anderson, J.W., Johnstone, B.M. & Cook-Newell, M.E. (1995). Meta-analysis of the effects of soy protein intake on serum lipids. New England Journal of Medicine, 333(5), pp.276–282.

Bazzano, L.A., He, J., Ogden, L.G., Loria, C., Vupputuri, S., Myers, L. & Whelton, P.K. (2001). Legume consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in US men and women. Archives of Internal Medicine, 161(21), pp.2573–2578.

Food and Agriculture Organization (2013). Dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition. Report of an FAO Expert Consultation. Rome: FAO.

Frias, J., Song, Y.S., Martínez-Villaluenga, C., González de Mejia, E. & Vidal-Valverde, C. (2008). Immunoreactivity and amino acid composition of fermented soybean products. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 56(1), pp.99–105.

Millward, D.J. (1999). The nutritional value of plant-based diets in relation to human amino acid and protein requirements. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 58(2), pp.249–260.

Morton, R.W., Murphy, K.T., McKellar, S.R., Schoenfeld, B.J., Henselmans, M., Helms, E., Aragon, A.A., Devries, M.C., Banfield, L., Krieger, J.W. & Phillips, S.M. (2018). A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(6), pp.376–384.

Phillips, S.M. & Van Loon, L.J.C. (2011). Dietary protein for athletes: From requirements to optimum adaptation. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(sup1), pp.S29–S38.

Tang, J.E., Moore, D.R., Kujbida, G.W., Tarnopolsky, M.A. & Phillips, S.M. (2009). Ingestion of whey hydrolysate, casein, or soy protein isolate: Effects on mixed muscle protein synthesis at rest and following resistance exercise in young men. Journal of Applied Physiology, 107(3), pp.987–992.

image sources

- vegan-energy-sources: Jeremy Reijnders