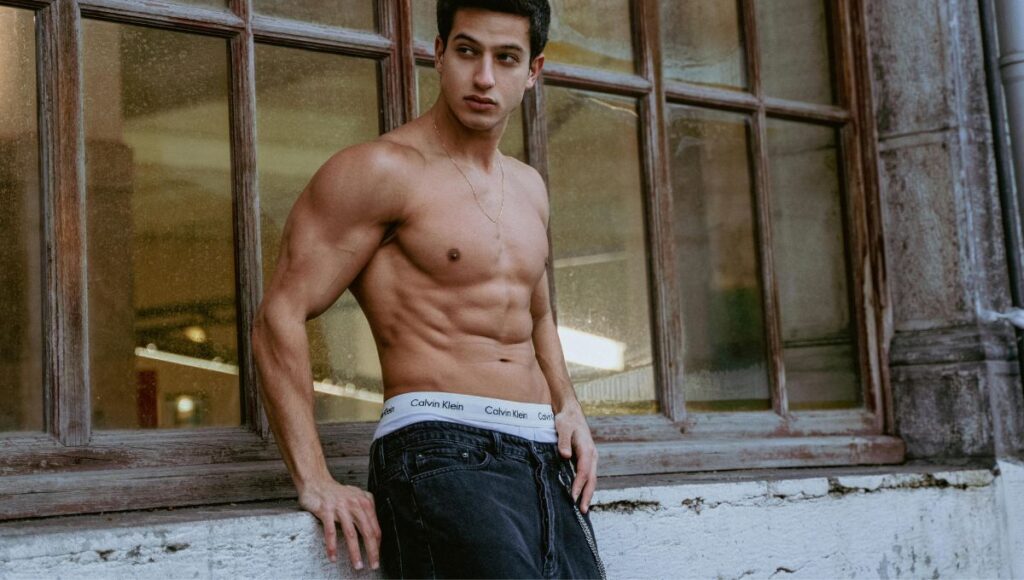

The rectus abdominis, commonly referred to as the “six-pack,” is a paired muscle that runs vertically on each side of the anterior wall of the human abdomen. It plays a crucial role in flexing the spinal column, stabilizing the core, and assisting with breathing movements. The muscle is segmented by tendinous intersections, which create the appearance of a six-pack when body fat is sufficiently low.

Developing visible abs without access to a gym requires a strategic combination of exercise, nutrition, and consistency.

[wpcode id=”229888″]

The Role of Body Fat in Ab Visibility

Contrary to popular belief, everyone has abdominal muscles; the issue is whether they are visible. The primary factor influencing visibility is body fat percentage. For most men, abdominal definition begins to show at around 10% body fat, and for women, at approximately 18% (Jackson & Pollock, 1978).

Reducing body fat through dietary control and increased energy expenditure is therefore essential.

Core Training Without Equipment

Bodyweight exercises are highly effective in targeting the abdominal muscles. They can be scaled in difficulty and are adaptable to different fitness levels. The following are evidence-based exercises for building core strength and abdominal muscle hypertrophy.

Plank Variations

Planks activate multiple core muscles simultaneously, including the rectus abdominis, transverse abdominis, and obliques (Ekstrom et al., 2007). Start with a standard forearm plank and progressively incorporate side planks, plank with shoulder taps, and plank-to-push-up transitions to increase difficulty.

Crunches and Sit-Ups

Although often criticized, traditional crunches have been shown to effectively target the rectus abdominis (Escamilla et al., 2010). For variation, include reverse crunches, bicycle crunches, and vertical leg crunches. These provide different angles of resistance and increased muscle activation.

Leg Raises and Hanging Knee Raises (Modified)

While hanging knee raises are gym-based, their alternatives like lying leg raises and seated leg lifts can be done at home. These exercises primarily target the lower region of the rectus abdominis. A study by Andersson et al. (1997) demonstrated high electromyographic (EMG) activation in the lower abs during such movements.

Hollow Body Hold

This is a gymnastics-inspired exercise that activates the entire abdominal region and enhances core endurance. It involves lying on the back, lifting the legs and shoulders off the ground, and holding the position. According to Hibbs et al. (2008), static holds are vital for developing isometric strength crucial for real-world movement stability.

Mountain Climbers and Flutter Kicks

These exercises combine core activation with cardiovascular stimulation, aiding in fat loss and muscular endurance. A study by Willardson (2007) emphasized the importance of integrating dynamic movements to train the core functionally.

Frequency and Volume of Training

Research suggests that training each muscle group at least twice per week leads to greater hypertrophy compared to once per week (Schoenfeld et al., 2016). For optimal results, perform core workouts 3 to 4 times weekly, incorporating different exercises each session. Aim for 3 to 4 sets of 12 to 20 repetitions per exercise. For static holds like planks, start with 30-second holds and build up to 2 minutes or more.

The Importance of Progressive Overload

Progressive overload is the gradual increase of stress placed on the muscles. This can be achieved by increasing reps, duration, or intensity. For bodyweight core training, methods include:

- Slowing down the eccentric (lowering) phase

- Reducing rest between sets

- Increasing time under tension

- Adding resistance using household items (e.g., water jugs)

According to Ratamess et al. (2009), progressive overload is key for muscular adaptations, regardless of the resistance source.

Nutrition: The Cornerstone of Fat Loss

No amount of ab training will reveal a six-pack if body fat remains high. A calorie deficit, where energy expenditure exceeds intake, is essential. Track daily caloric needs using the Mifflin-St Jeor Equation, then reduce intake by 10-20% for sustainable fat loss.

Macronutrient Distribution

- Protein: Essential for preserving muscle mass during a caloric deficit. Aim for 1.6 to 2.2 grams per kilogram of body weight per day (Morton et al., 2018).

- Carbohydrates: Fuel workouts and daily activities. Emphasize complex carbs like oats, brown rice, and vegetables.

- Fats: Support hormonal health. Include sources like avocados, nuts, and olive oil.

Intermittent Fasting and Abdominal Fat

Intermittent fasting (IF) can be a useful strategy to reduce caloric intake. A study by Tinsley and La Bounty (2015) found IF to be effective for fat loss and preserving lean mass. However, it is not superior to traditional calorie restriction and should be chosen based on personal preference.

Daily Activity and NEAT

Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) accounts for the calories burned during everyday activities. Increasing NEAT by walking more, standing instead of sitting, and doing household chores can significantly enhance fat loss (Levine, 2002).

Sleep and Recovery

Sleep deprivation increases ghrelin (hunger hormone) and decreases leptin (satiety hormone), leading to increased caloric intake (Spiegel et al., 2004). Aim for 7 to 9 hours of quality sleep per night to support hormonal balance and muscle recovery.

Stress and Cortisol Levels

Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which is associated with increased abdominal fat deposition (Epel et al., 2000). Manage stress through mindfulness, deep breathing, and physical activity to support fat loss and overall health.

Consistency Over Perfection

Results come from sustained effort, not perfection. Missing a workout or indulging occasionally will not derail progress if the overall lifestyle is in alignment with fitness goals. Set realistic expectations and measure progress through photos, measurements, and how clothes fit rather than scale weight alone.

Bibliography

Andersson, E.A., Nilsson, J., Ma, Z., Thorstensson, A. and Sjödin, B., 1997. Abdominal muscle recruitment during hip flexion exercises. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 78(3), pp.273-278.

Ekstrom, R.A., Donatelli, R.A. and Carp, K.C., 2007. Electromyographic analysis of core trunk, hip, and thigh muscles during 9 rehabilitation exercises. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 37(12), pp.754-762.

Escamilla, R.F., McTaggart, M.S., Fricklas, E.J., DeWitt, R., Kelleher, P., Taylor, M.K., Hreljac, A. and Moorman, C.T., 2010. An electromyographic analysis of commercial and common abdominal exercises: implications for rehabilitation and training. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 40(5), pp.265-276.

Epel, E., Lapidus, R., McEwen, B. and Brownell, K., 2000. Stress may add bite to appetite in women: a laboratory study of stress-induced cortisol and eating behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 26(1), pp.37-49.

Hibbs, A.E., Thompson, K.G., French, D.N., Wrigley, A. and Spears, I.R., 2008. Optimizing performance by improving core stability and core strength. Sports Medicine, 38(12), pp.995-1008.

Jackson, A.S. and Pollock, M.L., 1978. Generalized equations for predicting body density of men. British Journal of Nutrition, 40(3), pp.497-504.

Levine, J.A., 2002. Nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT): environment and biology. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 286(5), pp.E675-E685.

Morton, R.W., Murphy, K.T., McKellar, S.R., Schoenfeld, B.J., Henselmans, M., Helms, E., Aragon, A.A., Devries, M.C., Banfield, L. and Krieger, J.W., 2018. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(6), pp.376-384.

Ratamess, N.A., Alvar, B.A., Evetoch, T.K., Housh, T.J., Kibler, W.B., Kraemer, W.J. and Triplett, N.T., 2009. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 41(3), pp.687-708.

Schoenfeld, B.J., Ogborn, D. and Krieger, J.W., 2016. Effects of resistance training frequency on measures of muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 46(11), pp.1689-1697.

Spiegel, K., Tasali, E., Penev, P. and Van Cauter, E., 2004. Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Annals of Internal Medicine, 141(11), pp.846-850.

Tinsley, G.M. and La Bounty, P.M., 2015. Effects of intermittent fasting on body composition and clinical health markers in humans. Nutrition Reviews, 73(10), pp.661-674.

Willardson, J.M., 2007. Core stability training: applications to sports conditioning programs. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21(3), pp.979-985.

Key Takeaways Table

| Key Topic | Summary |

|---|---|

| Abdominal Muscle Visibility | Requires low body fat; around 10% for men, 18% for women |

| Effective Exercises | Planks, crunches, leg raises, mountain climbers, hollow body hold |

| Training Frequency | 3–4 sessions/week; 3–4 sets; 12–20 reps |

| Progressive Overload | Increase reps, time, reduce rest, or add resistance |

| Diet | Calorie deficit, high protein (1.6–2.2 g/kg), healthy fats, complex carbs |

| Intermittent Fasting | Optional tool for fat loss, not superior to calorie restriction |

| NEAT | Increase daily activity for more fat burn |

| Sleep and Recovery | 7–9 hours of sleep improves hormone balance and recovery |

| Stress Management | Reduces cortisol and supports fat loss |

| Consistency | Long-term effort is more important than short-term perfection |