As we move into our mid-30s and beyond, our training priorities and realities begin to shift. For many, lingering injuries become a persistent issue. Whether they stem from athletic pasts, occupational strain, or simply wear and tear, these injuries can derail consistency in training. However, muscle growth and strength gains are still achievable—even with physical limitations—if we adapt our approach intelligently.

Physiological changes with age include a reduction in joint resilience, a natural decline in anabolic hormone levels, and slower recovery. The combination of these factors means that pushing through pain or ignoring injury symptoms is riskier than it was in our 20s. To train effectively over 35, especially around injuries, requires a mindset shift: from chasing maximal effort to prioritizing sustainable intensity, biomechanical efficiency, and joint-friendly alternatives.

[wpcode id=”229888″]This article outlines science-backed strategies for safely building muscle around common injuries in adults over 35, and includes specific alternative exercises and methods that maintain or even enhance hypertrophy without worsening injury risk.

The Science of Aging and Injury

Muscle Mass Loss (Sarcopenia) and Its Impact

Sarcopenia is a condition characterized by age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength. According to Lexell et al. (1988), muscle mass begins to decline gradually after the age of 30 and accelerates after 60. Reduced muscle mass correlates strongly with loss of strength, lower metabolic rate, and increased risk of disability.

A 2013 study by Mitchell et al. demonstrated that type II fast-twitch fibers, which are critical for explosive strength and hypertrophy, are disproportionately affected with age. This decline underscores the importance of resistance training in older adults to preserve muscle and prevent frailty.

Injury Rates and Patterns Over 35

Middle-aged athletes often deal with specific injury patterns: rotator cuff strains, lumbar spine discomfort, patellofemoral pain syndrome, and Achilles tendinopathy are among the most common. These injuries are frequently chronic and exacerbated by poor movement patterns, overuse, or inadequate recovery. A study by Finnoff et al. (2011) found a strong association between repetitive high-load lifting in adults over 35 and overuse injuries in tendons and ligaments.

Hence, training strategies must evolve—not to eliminate load entirely, but to distribute it more intelligently.

Core Training Principles When Injured

1. Maintain Tension Without Load

The key to hypertrophy isn’t just heavy lifting—it’s mechanical tension. As noted by Schoenfeld (2010), muscle growth is primarily driven by three factors: mechanical tension, muscle damage, and metabolic stress. Of these, tension is the most fundamental and can be achieved through controlled tempo, isometric holds, and partial range movements, even at reduced loads.

2. Shift Focus to Pain-Free Ranges

Avoiding painful ranges of motion is crucial. Continuing to train into pain can aggravate inflammation and prolong healing. Instead, modifying joint angles, altering equipment, or choosing variations that shift the stress point can allow continued muscle activation without compromising safety.

3. Use Blood Flow Restriction (BFR) Training

BFR training involves using cuffs or bands to restrict venous return in the limbs during low-load resistance exercise. A meta-analysis by Hughes et al. (2017) confirmed that BFR at 20–30% 1RM can elicit similar hypertrophic responses to traditional high-load training. This makes it ideal for those with joint or tendon injuries that limit heavy lifting.

4. Prioritize Recovery Variables

Adults over 35 need more recovery—not less. Ensuring sufficient sleep, managing inflammation through nutrition, and using active recovery strategies such as mobility work and light aerobic sessions enhance tissue repair and reduce reinjury risk.

Injury-Specific Modifications and Alternatives

Shoulder Injuries (Rotator Cuff, Impingement)

Heavy overhead pressing, bench pressing, and snatches often exacerbate shoulder injuries. Instead:

- Replace barbell presses with landmine presses, which reduce shoulder abduction and limit impingement risk.

- Use neutral-grip dumbbell presses or Swiss bar to minimize stress on the glenohumeral joint.

- Focus on isometric lateral raises or cable Y-raises to train deltoids without aggressive joint rotation.

A study by Escamilla et al. (2009) highlighted the benefit of closed-chain push-up plus variations for maintaining shoulder function while minimizing strain.

Knee Pain (Patellofemoral Syndrome, Meniscus Issues)

Knees are prone to wear and tear in aging lifters, particularly when squatting deep or using heavy bilateral patterns. Modifications include:

- Sled pushes: Allow for quad engagement without eccentric joint loading.

- Step-ups and Bulgarian split squats: With controlled depth, these activate the quadriceps and glutes while reducing compressive joint forces.

- Terminal knee extensions (TKEs): These strengthen the VMO without full knee flexion, supporting knee alignment and stability.

A biomechanical study by Escamilla (2001) noted that front-loaded unilateral exercises generate less shear force on the knees compared to barbell back squats.

Lower Back Pain (Disc Bulge, Facet Joint Irritation)

Spinal injuries demand a shift from compressive axial loading to horizontal loading. Safer alternatives include:

- Belt squats: Load the legs while unloading the spine.

- Trap bar deadlifts with a neutral grip and elevated handles: Reduce lumbar shear and allow more hip-dominant leverage.

- Glute bridges and hip thrusts: Maximize posterior chain activation with minimal spinal stress.

In a 2015 EMG study by Contreras et al., hip thrusts produced equal or greater glute activation than squats while placing less strain on the lumbar spine.

Elbow and Wrist Pain (Tendinitis, Carpal Issues)

These areas are sensitive to grip-intensive, repetitive movements. Suggested adaptations:

- Use fat grips or lifting straps to reduce overuse strain during pulls.

- Opt for neutral-grip pull-ups or TRX rows instead of barbell rows or chin-ups.

- Replace barbell curls with cable curls or preacher curls using ergonomic attachments to reduce strain.

Research by Nirschl and Ashman (2003) underscores the importance of reducing eccentric overload during tendinopathy rehabilitation, supporting the switch to controlled concentric-dominant movements.

Programming Muscle Growth Around Limitations

Full-Body vs. Split Routines

Older lifters with injuries benefit from full-body routines 3–4 times per week. This approach allows for more frequent stimulation of muscles with less local fatigue per session, facilitating recovery and minimizing flare-ups.

A study by Schoenfeld et al. (2016) showed that higher frequency training (twice per muscle per week) led to better hypertrophy outcomes, even with equal volume, than once-a-week splits.

Exercise Rotation and Periodization

Cycling movements every 4–6 weeks reduces overuse strain and provides varied stimulus. Daily Undulating Periodization (DUP)—alternating hypertrophy, strength, and endurance rep schemes across the week—has been shown to yield superior results in older populations compared to linear progressions (Rhea et al., 2002).

Intensity and Effort Management

Avoid training to failure with compromised joints. Instead, stop 1–2 reps shy of failure (RIR method), using moderate loads and focusing on tempo. Studies by Lasevicius et al. (2018) demonstrate that leaving reps in reserve does not significantly blunt hypertrophy gains and can reduce injury risk.

Complementary Strategies for Recovery and Longevity

Anti-Inflammatory Nutrition

Foods high in omega-3 fatty acids (e.g., salmon, chia seeds), polyphenols (berries, green tea), and curcumin (turmeric) have been shown to reduce systemic inflammation. According to Mickleborough (2013), these dietary strategies improve joint health and may shorten recovery windows.

Supplementation

- Collagen and vitamin C pre-training have been associated with improved tendon health (Shaw et al., 2017).

- Creatine monohydrate enhances muscle mass and may support injury recovery through increased satellite cell activity (Candow et al., 2019).

- Magnesium and vitamin D support neuromuscular function and bone health, which are critical in aging athletes.

Mobility and Corrective Work

Incorporate 10–15 minutes daily of mobility focused on the hips, thoracic spine, and ankles. Foam rolling, banded joint distractions, and dynamic warm-ups should precede every session to prepare tissues. Cook et al. (2010) found that movement screen-based corrective work significantly reduced injury recurrence in trained populations.

Professional Assessment

Periodic sessions with physical therapists, chiropractors, or sports medicine practitioners help ensure that movement patterns are safe, and that any recurring pain is investigated early. Working around pain without understanding its root can lead to more severe breakdowns.

Conclusion: Training for the Long Game

Building muscle and maintaining strength over 35 is entirely achievable—even with chronic injuries—provided that training is adjusted to current capabilities, not past ego-driven standards. The body changes with age, but adaptation is still possible through smarter programming, scientific strategy, and a deeper understanding of individual limitations.

The key is to remain proactive, not reactive. Train intelligently, respect your body’s feedback, and use modern methods to create an environment where growth continues, safely and sustainably.

Bibliography

Candow, D.G., Chilibeck, P.D., Forbes, S.C. and Cornish, S.M., 2019. Creatine supplementation and aging musculoskeletal health. Frontiers in Nutrition, 6, p.124.

Contreras, B., Vigotsky, A.D., Schoenfeld, B.J., Beardsley, C. and Cronin, J., 2015. A comparison of gluteus maximus, biceps femoris, and vastus lateralis EMG amplitude between barbell hip thrusts and back squats. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 31(6), pp.452-458.

Cook, G., Burton, L., Hoogenboom, B. and Voight, M., 2010. Functional movement screening: the use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function—part 1. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 5(3), p.396.

Escamilla, R.F., 2001. Knee biomechanics of the dynamic squat exercise. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 33(1), pp.127-141.

Escamilla, R.F., Yamashiro, K., Paulos, L. and Andrews, J.R., 2009. Shoulder muscle activity and function in common shoulder rehabilitation exercises. Sports Medicine, 39(8), pp.663-685.

Finnoff, J.T., Coste, L. and Endres, N.K., 2011. Health care utilization and costs associated with sports injuries: a retrospective cohort study. PM&R, 3(7), pp.574-581.

Hughes, L., Paton, B., Rosenblatt, B., Gissane, C. and Patterson, S.D., 2017. Blood flow restriction training in clinical musculoskeletal rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(13), pp.1003-1011.

Lasevicius, T., Schoenfeld, B.J., Silva-Batista, C., Barros, T.S., Silva, M.F., Aihara, A.Y. and Ugrinowitsch, C., 2018. Muscle failure promotes greater muscle hypertrophy in low-load but not in high-load resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 33(1), pp.1-7.

Lexell, J., Taylor, C.C. and Sjöström, M., 1988. What is the cause of the ageing atrophy? Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 84(2-3), pp.275-294.

Mitchell, W.K., Williams, J., Atherton, P., Larvin, M., Lund, J. and Narici, M., 2013. Sarcopenia, dynapenia, and the impact of advancing age on human skeletal muscle size and strength; a quantitative review. Frontiers in Physiology, 4, p.260.

Mickleborough, T.D., 2013. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in physical performance optimization. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 23(1), pp.83-96.

Nirschl, R.P. and Ashman, E.S., 2003. Elbow tendinopathy: tennis elbow. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 22(4), pp.813-836.

Rhea, M.R., Ball, S.D., Phillips, W.T. and Burkett, L.N., 2002. A comparison of linear and daily undulating periodized programs with equated volume and intensity for strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 16(2), pp.250-255.

Schoenfeld, B.J., 2010. The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), pp.2857-2872.

Schoenfeld, B.J., Ogborn, D. and Krieger, J.W., 2016. Effects of resistance training frequency on measures of muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 46(11), pp.1689-1697.

Shaw, G., Lee-Barthel, A., Ross, M.L., Wang, B. and Baar, K., 2017. Vitamin C–enriched gelatin supplementation before intermittent activity augments collagen synthesis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 105(1), pp.136-143.

image sources

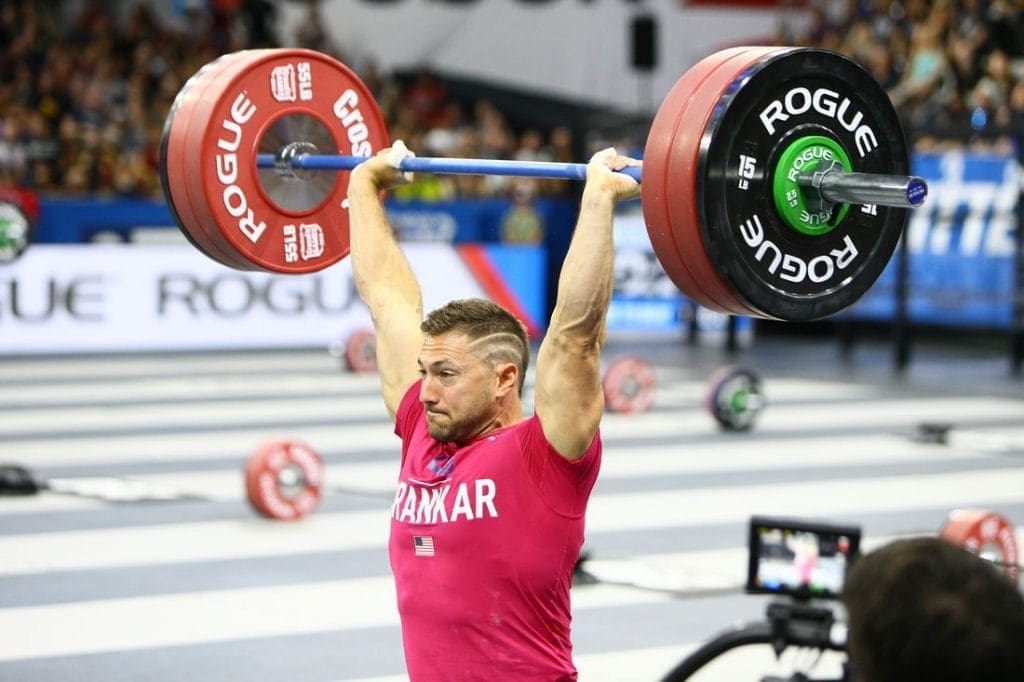

- Nick Urankar during Clean and Jerk Speed Ladder CF Games 2018: Photo courtesy of CrossFit Inc.