Building visible abdominal definition is a goal shared by many athletes and fitness enthusiasts. However, misconceptions often dominate the conversation, from over-reliance on endless crunch variations to underestimating the role of progressive overload and nutrition. To achieve a strong, defined six-pack, it is crucial to target the abdominal muscles with scientifically validated exercises that maximize activation, efficiency, and functional strength.

This article will break down the three best exercises for developing a six-pack, explain the anatomy and biomechanics behind each, and present evidence from peer-reviewed research. By the end, you will have a clear, actionable framework rooted in science rather than fitness myths.

Understanding Abdominal Anatomy and Function

The “six-pack” refers to the rectus abdominis, a long muscle running vertically along the front of the abdomen. It is divided by tendinous intersections, giving the segmented appearance when body fat levels are low. However, the rectus abdominis does not act in isolation.

Primary Muscles of the Core

- Rectus abdominis: Responsible for trunk flexion and stabilizing the pelvis.

- External obliques: Aid in trunk rotation and lateral flexion.

- Internal obliques: Work with external obliques for rotation and side bending.

- Transversus abdominis: Provides deep core stability, functioning like a natural weight belt.

- Erector spinae and multifidus: Located posteriorly, these maintain spinal stability and balance the anterior core.

Research highlights that the core’s primary role extends beyond flexion. It provides stability, resists unwanted movement, and transfers force during athletic tasks (McGill, 2010). Therefore, effective abdominal training must go beyond superficial aesthetics and train the abs in their functional context.

The 3 Best Exercises for a Great Six Pack

After evaluating electromyography (EMG) data and functional demands, the three best exercises are:

- Hanging Leg Raise

- Ab Wheel Rollout

- Cable Crunch

These movements combine high muscle activation, progressive overload potential, and practical carryover to athletic performance.

Exercise 1: Hanging Leg Raise

Why It Works

The hanging leg raise is one of the most effective exercises for recruiting the lower portion of the rectus abdominis and hip flexors. By starting from a hanging position, the exercise also demands significant stabilization from the shoulders, lats, and grip strength, making it a compound core-builder.

Scientific Evidence

A study by Andersson et al. (1997) found that hanging leg raises produced higher rectus abdominis activation compared to traditional floor-based exercises like crunches. EMG analyses consistently demonstrate superior lower-abdominal involvement during vertical hip flexion tasks.

Proper Technique

- Hang from a pull-up bar with arms fully extended.

- Keep your torso stable, avoid swinging.

- Flex at the hips and lift your knees toward your chest, or extend the legs for increased difficulty.

- Lower under control to full extension.

Common Mistakes

- Using momentum instead of controlled muscle contraction.

- Arching the lower back, which reduces abdominal involvement and stresses the lumbar spine.

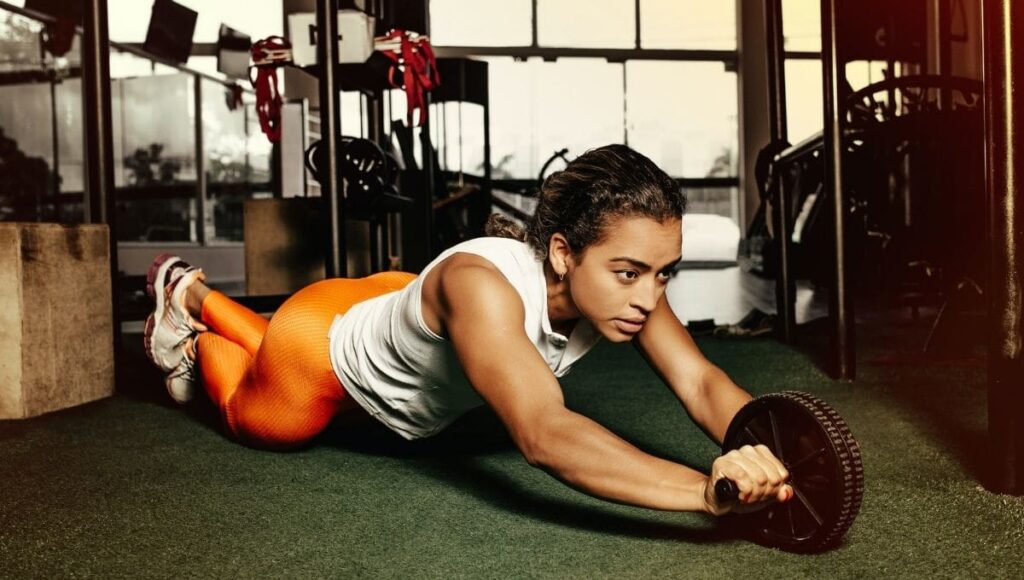

Exercise 2: Ab Wheel Rollout

Why It Works

The ab wheel rollout primarily trains the rectus abdominis in an anti-extension role, resisting spinal hyperextension. This functionally replicates how the core stabilizes the spine during athletic performance and heavy lifts like squats and deadlifts.

Scientific Evidence

Escamilla et al. (2010) demonstrated that rollout-type exercises activate both the rectus abdominis and obliques at high intensities. The ab wheel is comparable to advanced stability ball rollouts, but allows greater range of motion and loading potential.

Proper Technique

- Kneel on the floor with the ab wheel directly in front of you.

- Roll forward slowly, keeping the spine neutral.

- Extend as far as control allows without letting the lower back sag.

- Pull the wheel back using core tension, not hip flexors.

Common Mistakes

- Overarching the spine, leading to lumbar strain.

- Rolling too quickly, which reduces time under tension.

- Limited range of motion due to insufficient progression.

Exercise 3: Cable Crunch

Why It Works

Unlike many ab exercises, the cable crunch allows progressive overload by adjusting the resistance stack. This provides mechanical tension, a key driver of hypertrophy (Schoenfeld, 2010). It directly trains spinal flexion under load, heavily recruiting the rectus abdominis.

Scientific Evidence

Research shows that loaded spinal flexion movements, when performed correctly, achieve high rectus abdominis activation without compromising safety (Konrad et al., 2001). EMG data indicates that weighted crunches surpass bodyweight variations in muscle recruitment, especially in advanced trainees.

Proper Technique

- Kneel in front of a high pulley with a rope attachment.

- Hold the rope behind your head or at the sides of your shoulders.

- Flex the spine downward, bringing your elbows toward the floor.

- Slowly return to the starting position under control.

Common Mistakes

- Moving primarily at the hips instead of the spine.

- Using excessive weight, reducing range of motion.

- Pulling with arms instead of initiating from the abs.

Training Principles for Six-Pack Development

Progressive Overload

As with any muscle group, abdominal hypertrophy requires gradually increasing resistance or volume. Relying on high-rep, low-intensity crunches does not provide sufficient stimulus.

Frequency and Recovery

Two to three dedicated core sessions per week are sufficient. Overtraining the abs daily can impair recovery without enhancing results.

Body Fat Levels

Visible abs depend not only on muscle development but also on reducing subcutaneous fat. For men, abdominal definition typically appears at 10–12% body fat; for women, around 18–20% (Heymsfield et al., 2005).

Integration into Training

These exercises should complement, not replace, compound lifts like squats, deadlifts, and overhead presses, which also demand core stability.

Conclusion

The pursuit of a six-pack requires strategic exercise selection, progression, and consistency. The hanging leg raise, ab wheel rollout, and cable crunch represent the most effective combination of movements for building a defined and functional rectus abdominis. Backed by electromyographic and biomechanical evidence, these exercises should form the foundation of any serious ab training program.

Key Takeaways

| Exercise | Primary Benefit | Scientific Support | Key Coaching Cue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hanging Leg Raise | Strong lower-ab activation, stability | Andersson et al., 1997 | Avoid swinging, control motion |

| Ab Wheel Rollout | Anti-extension strength, deep stability | Escamilla et al., 2010 | Keep spine neutral, resist arching |

| Cable Crunch | Progressive overload for hypertrophy | Konrad et al., 2001; Schoenfeld, 2010 | Initiate flexion from abs, not hips |

Bibliography

- Andersson, E.A., Ma, Z., Thorstensson, A. (1997). Relative EMG levels in abdominal muscles during planks and leg lifts. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 7(2), 82–88.

- Escamilla, R.F., Babb, E., DeWitt, R., Jew, P., Kelleher, P., Burnham, T., Busch, J. (2010). Electromyographic analysis of traditional and nontraditional abdominal exercises: Implications for rehabilitation and training. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 40(5), 265–276.

- Heymsfield, S.B., Lohman, T.G., Wang, Z., Going, S.B. (2005). Human Body Composition. 2nd ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Konrad, P., Schmitz, K., Denner, A. (2001). EMG analysis of abdominal muscle activity in various abdominal exercises. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 11(6), 441–447.

- McGill, S.M. (2010). Ultimate Back Fitness and Performance. 4th ed. Waterloo, Canada: Backfitpro.

- Schoenfeld, B.J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857–2872.

image sources

- Ab wheel: Jonathan Borba / Unsplash