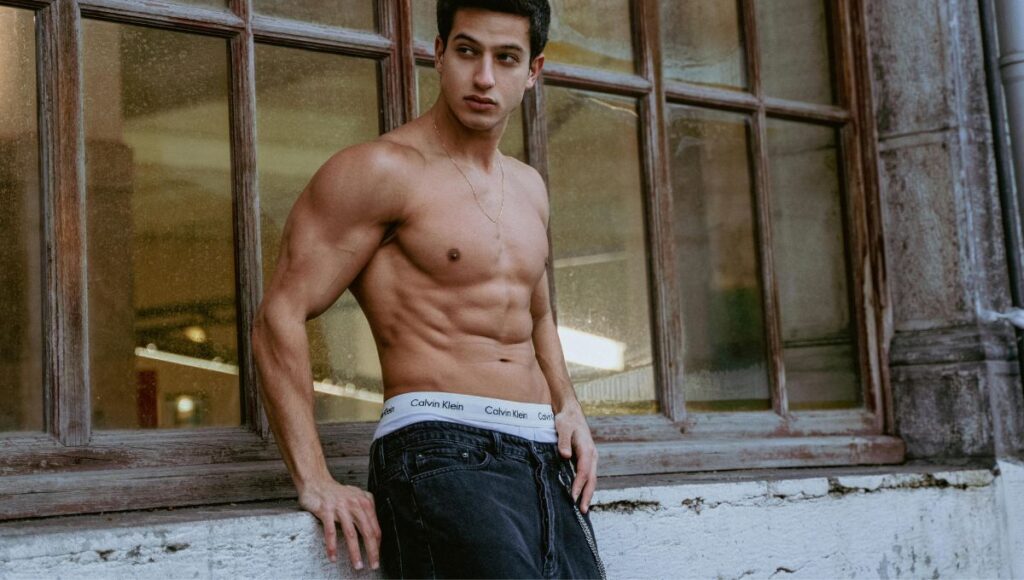

The pursuit of visible abdominal muscles—often referred to as a “six-pack”—is one of the most common fitness goals. Traditional wisdom places sit ups and crunches at the center of ab training, but science reveals that these exercises are neither necessary nor the most effective approach.

This article examines whether you can build a six pack without sit ups, drawing on scientific evidence about muscle activation, fat loss, and training efficiency.

Understanding What a Six Pack Really Is

Anatomy of the Rectus Abdominis

The six pack refers to the rectus abdominis, a long muscle that runs vertically along the front of the abdomen. Its segmented appearance comes from connective tissue bands that divide it into sections. However, visibility depends primarily on body fat levels rather than muscle size alone (McGill, 2010).

Body Fat and Muscle Definition

Research shows that for abdominal definition to be visible, men typically need to reach approximately 10–15% body fat, while women usually need to reach around 18–22% (Heymsfield et al., 2015). This highlights that nutrition and fat loss play a greater role than endless sit ups.

Why Sit Ups Are Not Essential

Limited Muscle Activation

Sit ups primarily target the rectus abdominis through spinal flexion. However, electromyographic (EMG) studies indicate that planks, hanging leg raises, and rollouts produce greater core activation across multiple abdominal muscles (Escamilla et al., 2010).

Risk of Spinal Stress

Repeated spinal flexion under load, as in sit ups, has been linked to increased risk of lumbar disc injury (Callaghan & McGill, 2001). This makes sit ups less desirable compared to core exercises that maintain a neutral spine.

Alternative Science-Backed Abdominal Exercises

Planks and Variations

Planks activate not only the rectus abdominis but also the transverse abdominis and obliques, providing a more comprehensive core stimulus. A study by Ekstrom et al. (2007) showed significantly higher deep core activation compared to sit ups.

Hanging Leg Raises

Hanging leg raises produce high levels of rectus abdominis and hip flexor activation. Research by Youdas et al. (2008) found them superior to sit ups in activating lower abdominal regions.

Ab Rollouts

Ab rollouts performed with a wheel or barbell create high demands on the core to resist lumbar extension. Comfort et al. (2011) demonstrated greater rectus abdominis activation compared to traditional sit ups.

Anti-Rotation and Stability Exercises

Movements like Pallof presses train the core to resist unwanted motion, engaging deeper stabilizing muscles. This functional training is associated with improved performance and injury prevention (Behm et al., 2010).

The Role of Compound Lifts

Squats and Deadlifts

Heavy compound lifts like squats and deadlifts require high levels of trunk stiffness and core activation to stabilize the spine. EMG data confirm that these lifts strongly activate the rectus abdominis and obliques (Hamlyn et al., 2007).

Overhead Presses and Carries

Loaded carries (e.g., farmer’s carries) and overhead presses further engage the core muscles isometrically. This builds abdominal strength in a more functional context than sit ups.

Nutrition: The Decisive Factor

Caloric Deficit and Fat Loss

No matter how strong your abdominal muscles are, they remain hidden under fat if nutrition is neglected. A caloric deficit achieved through diet is the primary driver of fat loss (Hall et al., 2016).

Protein Intake

Higher protein intake supports muscle retention and satiety during fat loss. A daily intake of 1.6–2.2 g of protein per kilogram of body weight is recommended for optimal body composition (Morton et al., 2018).

Macronutrient Balance

While the calorie deficit is most critical, evidence suggests that higher protein and balanced fat/carbohydrate intake support adherence and long-term success (Antonio et al., 2014).

Cardio and Energy Expenditure

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT)

HIIT has been shown to be more time-efficient than steady-state cardio for fat loss, while also preserving lean muscle (Boutcher, 2011). This makes it an effective complement to strength training.

Steady-State Cardio

Moderate-intensity steady-state cardio remains a useful tool for overall calorie expenditure and recovery, though it is less efficient per unit of time compared to HIIT.

The Role of Genetics

Muscle Shape and Tendinous Inscriptions

The appearance of a six pack is largely influenced by genetics. Tendinous inscriptions determine how many “packs” are visible, and muscle shape cannot be changed with training (Katch et al., 2011).

Fat Distribution

Some individuals store more fat in the abdominal region due to hormonal and genetic factors, making abdominal definition harder to achieve despite low overall body fat (Karastergiou et al., 2012).

A Practical Framework to Build a Six Pack Without Sit Ups

Step 1: Prioritize Compound Lifts

Train with squats, deadlifts, presses, and carries to build core strength in a functional manner.

Step 2: Add Targeted Core Work

Incorporate planks, rollouts, hanging leg raises, and anti-rotation exercises 2–3 times per week.

Step 3: Manage Nutrition

Maintain a consistent calorie deficit, focus on protein intake, and sustain long-term dietary adherence.

Step 4: Include Conditioning

Use HIIT or steady-state cardio to support energy expenditure.

Step 5: Allow for Recovery

Adequate sleep and recovery are essential for hormonal balance and fat loss (Leproult & Van Cauter, 2010).

Key Takeaways

| Principle | Scientific Basis | Practical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sit ups are not necessary | Sit ups have lower EMG activation and higher spinal risk | Replace with planks, rollouts, leg raises |

| Core strength comes from multiple muscles | Deeper core muscles engaged in stability work | Include anti-rotation and stability exercises |

| Compound lifts train the core | Squats and deadlifts activate abs significantly | Prioritize heavy compound lifts |

| Nutrition is decisive for visibility | Fat loss enables abs to show | Maintain a calorie deficit with high protein |

| Cardio supports fat loss | HIIT is efficient, steady-state adds volume | Use both for optimal results |

| Genetics affect six pack appearance | Tendinous inscriptions and fat distribution | Focus on controllable factors like training and diet |

References

- Antonio, J., et al. (2014). A high protein diet has no harmful effects: a one-year crossover study in resistance-trained males. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2014, 1–5.

- Behm, D. G., Drinkwater, E. J., Willardson, J. M., & Cowley, P. M. (2010). Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology position stand: The use of instability to train the core in athletic and nonathletic conditioning. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 35(1), 109–112.

- Boutcher, S. H. (2011). High-intensity intermittent exercise and fat loss. Journal of Obesity, 2011, 1–10.

- Callaghan, J. P., & McGill, S. M. (2001). Low back joint loading and kinematics during standing and unsupported sitting. Ergonomics, 44(3), 280–294.

- Comfort, P., Pearson, S. J., & Mather, D. (2011). An electromyographic comparison of trunk muscle activity during isometric trunk and dynamic strengthening exercises. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(1), 149–154.

- Ekstrom, R. A., Donatelli, R. A., & Carp, K. C. (2007). Electromyographic analysis of core trunk, hip, and thigh muscles during 9 rehabilitation exercises. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 37(12), 754–762.

- Escamilla, R. F., et al. (2010). Core muscle activation during Swiss ball and traditional abdominal exercises. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 40(5), 265–276.

- Hall, K. D., et al. (2016). Energy balance and its components: Implications for body weight regulation. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 104(3), 989–1003.

- Hamlyn, N., Behm, D. G., & Young, W. B. (2007). Trunk muscle activation during dynamic weight-training exercises and isometric instability activities. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21(4), 1108–1112.

- Heymsfield, S. B., et al. (2015). Body mass index as a measure of body fatness: Age- and sex-specific prediction formulas. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 102(3), 796–808.

- Karastergiou, K., et al. (2012). Sex differences in human adipose tissues – the biology of pear shape. Biology of Sex Differences, 3(1), 13.

- Katch, F. I., et al. (2011). Exercise Physiology: Energy, Nutrition, and Human Performance. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Leproult, R., & Van Cauter, E. (2010). Role of sleep and sleep loss in hormonal release and metabolism. Endocrine Development, 17, 11–21.

- McGill, S. M. (2010). Core training: Evidence translating to better performance and injury prevention. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 32(3), 33–46.

- Morton, R. W., et al. (2018). Protein intake to maximize whole-body anabolism during postexercise recovery. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 108(2), 267–276.

- Youdas, J. W., et al. (2008). Magnitude of muscle activation during abdominal strengthening exercises using portable abdominal exercise devices. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 38(5), 265–276.