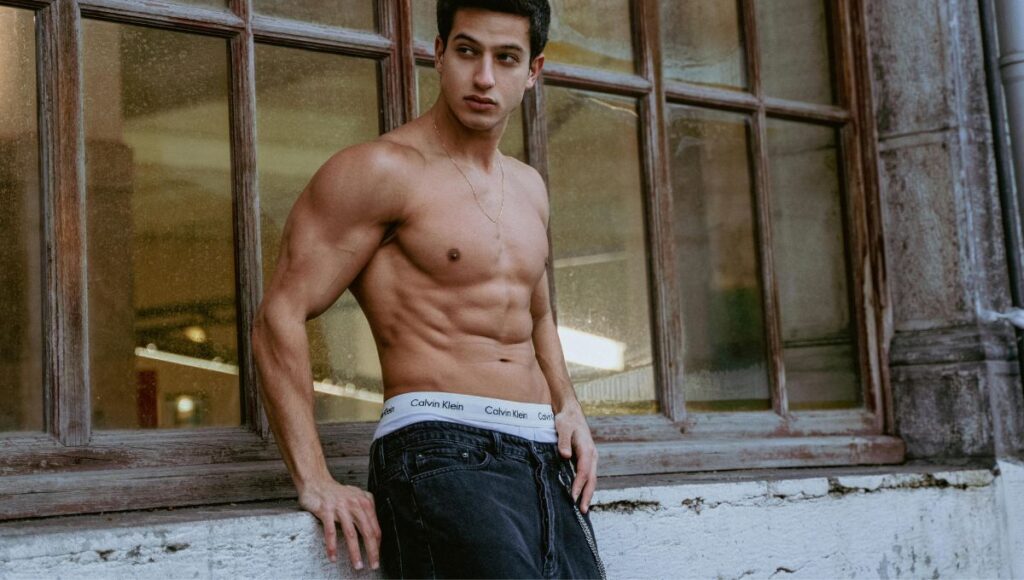

Building a six pack is one of the most common goals in fitness. Yet, many people waste years doing ineffective exercises, chasing “quick fix” programs, or following outdated advice.

To achieve a visible six pack, you need both low body fat and highly developed abdominal muscles. While diet plays a major role in reducing fat, the other half of the equation is selecting workouts that truly stimulate abdominal growth.

This article explores three science-backed ab workouts that actually build a six pack. Unlike traditional crunches or fad ab machines, these workouts are proven to target deep core musculature, increase strength, and produce the hypertrophy necessary for visible definition. We will analyze each workout in detail, explain why it works, and back every claim with scientific evidence.

Understanding the Science of Ab Hypertrophy

The Anatomy of the Abdominal Muscles

The abdominal region is not a single muscle but a group of interconnected muscles:

- Rectus abdominis: The “six pack” muscle responsible for spinal flexion.

- External obliques: Located on the sides of the torso, critical for rotation and lateral flexion.

- Internal obliques: Underneath the external obliques, stabilizing and assisting in rotation.

- Transverse abdominis: The deepest core muscle, acting like a corset to stabilize the spine.

For visible definition, the rectus abdominis must be hypertrophied, but functional strength and aesthetics also depend on obliques and transverse activation.

Why Traditional Crunches Aren’t Enough

Crunches and sit-ups isolate the rectus abdominis but do not create enough progressive overload to stimulate significant hypertrophy. Electromyographic (EMG) research shows that while crunches activate the rectus, they underload deeper core stabilizers compared to compound lifts and anti-rotation exercises (Escamilla et al., 2010). Over-relying on crunches may also increase spinal flexion stress without improving functional strength.

Hypertrophy Principles for Ab Training

The same rules that apply to other muscles apply to ab development:

- Progressive overload: Increasing resistance or complexity is essential.

- Time under tension: Slower eccentrics and controlled movement increase stimulus.

- Training frequency: Abs recover quickly, allowing 2–4 sessions per week.

- Variety of planes: Training flexion, rotation, and anti-extension produces balanced development.

Workout 1: Weighted Compound Core Integration

Why It Works

Heavy compound lifts are among the most effective ab developers. Studies show squats, deadlifts, and overhead presses engage the rectus abdominis and obliques at high levels (Hamlyn et al., 2007). Unlike isolation moves, these lifts force the abs to stabilize heavy loads, promoting hypertrophy.

Key Exercises

- Front Squat (4×6–8)

EMG research confirms front squats demand more abdominal activation than back squats due to anterior bar placement (Gullet et al., 2009). This makes them excellent for six pack development. - Overhead Press (3×8–10)

Maintaining a rigid torso under vertical load requires the transverse abdominis and obliques to stabilize the spine. - Trap Bar Deadlift (4×6)

Engages the entire core to resist spinal flexion. Adding pauses mid-lift increases time under tension.

Training Notes

- Prioritize progressive overload by adding weight each week.

- Maintain a braced core and avoid excessive lumbar extension.

Workout 2: Direct Ab Hypertrophy Circuit

Why It Works

Direct ab training ensures localized hypertrophy of the rectus and obliques. EMG data shows that weighted ab exercises outperform bodyweight-only movements in stimulating muscle fibers (Lehman et al., 2005). This circuit focuses on spinal flexion, anti-extension, and rotation.

The Circuit

Perform 3–4 rounds, resting 60 seconds between rounds.

- Cable Crunch (12–15 reps)

Provides constant tension and allows progressive loading. Focus on flexing the spine, not hinging at the hips. - Hanging Leg Raise (10–12 reps)

Targets the lower rectus and hip flexors. Keeping legs straight increases difficulty and abdominal activation (Andersson et al., 1997). - Ab Wheel Rollout (8–12 reps)

One of the most effective anti-extension exercises. EMG data confirms superior transverse abdominis activation compared to crunches (Escamilla et al., 2010). - Pallof Press (10 reps per side)

A proven anti-rotation exercise that strengthens obliques and deep core stabilizers.

Training Notes

- Use controlled tempo (2s eccentric, 1s concentric).

- Add weight gradually to maintain progressive overload.

Workout 3: Functional Athletic Core Training

Why It Works

Functional ab training combines stability, rotation, and power transfer. Athletes require strong cores to transfer force between upper and lower body. Research highlights that anti-rotation and dynamic movements like chops and throws activate both rectus and obliques (Behm et al., 2010).

Key Exercises

- Landmine Rotation (3×10 per side)

A loaded rotational movement developing obliques and transverse abdominis. Best performed explosively. - Medicine Ball Slam (4×8)

High-velocity power training for the abs. Research shows explosive core movements improve both strength and hypertrophy (Sato & Mokha, 2009). - Farmer’s Carry (3x40m)

A loaded carry that challenges the entire core to resist lateral flexion. Side carries increase oblique emphasis. - Single-Arm Cable Chop (3×12 per side)

Mimics athletic movement patterns and strengthens rotational control.

Training Notes

- Emphasize proper bracing and movement efficiency.

- Prioritize explosive intent for slams and rotations.

Programming Your Ab Workouts

Frequency

For hypertrophy, train abs 2–4 times weekly. Split between compound, hypertrophy circuits, and functional training.

Integration with Other Training

- Place ab-specific work at the end of sessions to avoid fatigue during heavy lifts.

- Rotate workouts to cover all planes of motion: flexion, rotation, anti-extension, and lateral stability.

Nutrition and Body Fat

Even the strongest abs won’t be visible under high body fat. Studies suggest men generally need to reach 10–15% body fat and women 16–22% for abdominal definition (Gallagher et al., 2000). Protein intake of 1.6–2.2 g/kg/day supports muscle hypertrophy (Morton et al., 2018).

Common Mistakes That Prevent Six Pack Development

- Relying only on crunches: Limits stimulus to rectus only.

- No progressive overload: Treating abs differently from other muscles hinders growth.

- Excessive daily ab training: Overtraining without recovery impairs hypertrophy.

- Ignoring diet: Even perfectly trained abs won’t show without caloric control.

Conclusion

To build a six pack, you must combine resistance-based hypertrophy training with a fat-loss strategy. The three workouts outlined here—weighted compound integration, direct hypertrophy circuits, and functional athletic training—cover all aspects of ab development. By applying principles of progressive overload, variety, and scientific programming, you can achieve both strength and aesthetics in your core.

Key Takeaways

| Principle | Why It Matters | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Progressive overload | Essential for ab hypertrophy | Add weight to cable crunches |

| Variety of movement planes | Ensures complete development | Combine flexion, anti-rotation, carries |

| Compound lifts | Recruit abs under heavy load | Front squats, overhead press |

| Direct isolation | Hypertrophies rectus and obliques | Hanging leg raises, ab wheel |

| Functional training | Improves rotation and stability | Landmine rotations, carries |

| Nutrition | Required for visible abs | Maintain 10–15% body fat (men) |

References

- Andersson, E.A., Ma, Z., Thorstensson, A. (1997). Relative EMG levels in abdominal muscles during partial curl-ups. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 7(1), pp.42-48.

- Behm, D.G., Drinkwater, E.J., Willardson, J.M., Cowley, P.M. (2010). Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology position stand: the use of instability to train the core in athletic and nonathletic conditioning. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 35(1), pp.109-112.

- Escamilla, R.F., Babb, E., DeWitt, R., Jew, P., Kelleher, P., Burnham, T., Mowbray, R., Imamura, R. (2010). Electromyographic analysis of traditional and nontraditional abdominal exercises: implications for rehabilitation and training. Physical Therapy, 90(5), pp.698-711.

- Gallagher, D., Heymsfield, S.B., Heo, M., Jebb, S.A., Murgatroyd, P.R., Sakamoto, Y. (2000). Healthy percentage body fat ranges: an approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 72(3), pp.694-701.

- Gullett, J.C., Tillman, M.D., Gutierrez, G.M., Chow, J.W. (2009). A biomechanical comparison of back and front squats in healthy trained individuals. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(1), pp.284-292.

- Hamlyn, N., Behm, D.G., Young, W.B. (2007). Trunk muscle activation during dynamic weight-training exercises and isometric instability activities. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21(4), pp.1108-1112.

- Lehman, G.J., Gordon, T., Langley, J., Pemrose, P., Tregaskis, S. (2005). Replacing sit-ups with core stabilization exercises: a comparative EMG analysis. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 19(4), pp.949-953.

- Morton, R.W., Murphy, K.T., McKellar, S.R., Schoenfeld, B.J., Henselmans, M., Helms, E., Aragon, A.A., Devries, M.C., Banfield, L., Krieger, J.W., Phillips, S.M. (2018). A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(6), pp.376-384.

- Sato, K., Mokha, M. (2009). Does core strength training influence running kinetics, lower-extremity stability, and 5000-M performance in runners? Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(1), pp.133-140.